The series was based on Wiltshire’s second novel, Child of Vodyanoi; published in 1978, it followed hot on the heels of his first, The Homosaur. Both are ‘monster on the loose’ stories; The Homosaur’s plot revolves around an implausibly humanoid dinosaur hatched out in modern-day Bedfordshire. (My main memory of it is that the protagonist and his wife have something of a spanking fetish; make of that what you will.)

Police Inspector Inskip enlists the aid of both Dunlop and his girlfriend Fiona. Both the blizzard sweeping across the island and the level of radiation the killer leaves in its wake should have killed any normal man by now, but the murders continue: the killer appears to be both more and less than human. And then a squad of paratroopers, led by the mysterious Major Howard, arrive on the island …

Unlike The Homosaur, Child of Vodyanoi keeps the reader in the dark about the killer’s origins and rationale up till the climax, focusing on the shadowy, inhuman slayer stalking the island and the hunt for it. And those origins are far more disturbingly plausible, rooted in the tensions and technology of the Cold War: a nuclear accident and malfunctioning cybernetic equipment have turned a Soviet submariner into a homicidal madman, dying in agony–yet, until the end comes, almost unstoppable.

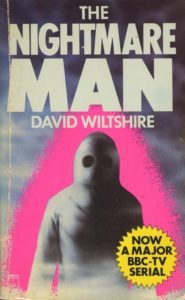

Holmes stuck fairly closely to Wiltshire’s plot, though with a handful of significant changes. Child of Vodyanoi became The Nightmare Man – a title Wiltshire had discarded for the novel–while Major Howard became Colonel Howard, and arrived on the island in the very first episode. The sexual assault on Sheila Anderson was dropped, as was a subplot about Fiona’s estranged husband. Most tellingly, where Wiltshire offers us a few brief glimpses of the killer before the climax, Holmes keeps the monster almost entirely unseen until the very end. Most of the killer’s actions are viewed from its point of view, through a blood-red haze, accompanied by rasping, slobbering breaths – and at one point, when one of the murders is caught on tape, by grotesque, demented laughter.

The casting is something of a roll-call of genre TV stalwarts of the period: James Warwick, who specialised in lantern-jawed stiff-upper-lip heroes, played Dunlop (now renamed Michael Gaffikin), with Maurice Roeves as Inskip and James Cosmo (now better known as Jeor Mormont in Game Of Thrones) as his trusty sidekick Sergeant Carch. Jonathan Newth played the enigmatic Colonel Howard, with Tom Watson as the crusty local GP, Dr Goudry. Fiona was played by Celia Imrie in one of her first roles; best known for her comedy work, Imrie is as always excellent, if underused.

The killer was played by Pat Gorman, who’s something of an unsung hero of 1970s and ‘80s British TV: never cast in a lead role, he played a host of bit and supporting characters over the years, appearing in no less than 83 episodes of Dr Who alone.

Finally, the director was Douglas Camfield, another Who veteran known for being able to create a powerful drama with minimal resources. Unusually for the time, The Nightmare Man was filmed entirely on location and on videotape, with Port Isaac in Cornwall standing in for the Outer Hebrides.

Overall, the mood’s somewhere between that of a classic Hammer film (think Quatermass and the Pit or Planet Films’ Island Of Terror rather than Dracula or Curse of Frankenstein) and Philip Hinchcliffe-era Dr Who at its grimmest.

The epigraph to Child Of Vodyanoi is an excerpt from the old Henry Hall song: “Hush, hush, hush, here comes the Bogey Man …” That’s what really makes The Nightmare Man work; the killer is the Bogey Man, that primal figure of dread. The monster that waits in the dark outside, trying to come in and claim us.

But like so many things that scared me in childhood, the real thing doesn’t measure up to the idea of the monster in my head: something horrible and pitiful all at once, terrifying and heartrending. And something that combines the pitiless strength of the robot run amok with the bestial savagery of the werewolf.

Just make sure your doors and windows are locked against the night before settling down with it.

SIMON BESTWICK