“A mixed bag that will entertain die hard genre fans!”

“A mixed bag that will entertain die hard genre fans!”

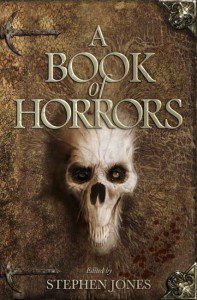

This imposing trade paperback anthology from Jo Fletcher Books (St. Martin’s Press in the US) boasts an impressive roster of international talent, including Stephen King, Dennis Etchison, Ramsey Campbell, John Ajvide Lindqvist, Richard Christian Matheson, Michael Marshall Smith and Lisa Tuttle. Here rubbing shoulders are New York Times bestsellers and winners of the World Fantasy, Bram Stoker, Nebula and John W. Campbell awards. According to the publicity blurb it has been lauded by Publishers Weekly, Booklist and SFX, among others, and is touted as ‘…the most critically acclaimed horror anthology of recent years…’ To add decibels to the fanfare, editor Stephen Jones’ introduction throws down a gauntlet to other anthologies and to the field as a whole; its provocative title an open question: ‘Whatever Happened to Horror?’

The clear message is that all is not well with the genre and this book’s mission is nothing less than to put the situation to rights. In adopting such a bold stance the editor appears supremely confident that the reader will accept his claims about horror’s anaemic decline and his anthology’s reinfusion at face value. This is questionable on both counts. The genre has certainly seen an onslaught of mainstream ‘horror-lite’ product which Jones refers to, but shifting units has long been the measure of success in an industry which has targeted a wider, younger readership by softening its product – Jones might use the term “dumbing down” – yet plenty of writers with a more adult appeal still thrive alongside their youthfully glowing counterparts. (This broadening of appeal is not limited to horror: science fiction has been on the wane since the 70s and on high street shelves it has long struggled to survive its parasitic cousin, fantasy; but, again, several talented practitioners keep the starfires burning despite its burial beneath a purple avalanche.) One could argue that ‘horror-heavy’ is in fact in robust rude health and that the works of some contributors to this anthology plus many other exciting writers (both ‘new’ and ‘old’) provide ample evidence of this.

And, even if one accepts Jones’ diagnosis, does the substance of his claim that the ‘fight back’ begins here match the rhetoric? Well, let’s see.

Stephen King’s ‘The Little Green God of Agony’ is a modern spin on exorcism in which the Reverend Rideout, a strange and intense Arkansas minister, is engaged by bedridden multimillionaire Andrew Newsome to cure him after all the medical expertise his wealth can buy has failed to alleviate his extreme pain. The events unfold through the eyes of Kat, Newsome’s sceptical nurse, who has come to believe that her patients are all malingerers and is certain Rideout (Devil Ride(s)out, geddit?) is a charlatan out to lay his hands on a large chunk of Newsome’s fortune. This provides a solid start but few fireworks; a master storyteller’s touch heats up lukewarm material and King springs a neat reversal as Rideout wounds Kat with preceptively barbed home truths before joining battle with the pain-demon lurking inside Newsome. The reader is held at arm’s length though and not drawn in fully until the end, and at 30 pages it’s a touch long. Had it featured in King’s last collection, Just After Sunset, it wouldn’t have been the weakest piece on show, but neither would it have been among the best.

Caitlin R. Kiernan’s ‘Charcloth, Firesteel and Flint’ is among a handful of stories that don’t match up to the hyperbole. As much fantasy as horror, it’s a yarn of an ancient elemental time wanderer who lives only to deliver fire, in the guise of a sexually attractive young woman (one wonders at the reaction to this had the author been male). While walking beside a Midwestern highway at midnight she is picked up by Billy, who tells her he’s heading for Sioux City. They drive, have a very long conversation about fire, go to a motel and… well, that would be telling. This tale fails to convince and creaks under the weight of backstory, resulting in way too much being told instead of shown. Although the dénouement inverts expectation, it’s ultimately underwhelming because one doesn’t care enough about the characters for it to matter.

‘The Coffin-Maker’s Daughter’ by Angela Slatter also teeters uncomfortably between fantasy and horror. The characterisation is strong and the black comic tone enticing, but the ending is predictable and punctures the good work of the build-up.

Dennis Etchison’s ‘Tell Me I’ll See You Again’ is a mood piece about the blurring of lines between the pretence of being dead and the actuality of death, but it’s just too opaque in the execution and again lacks that complete 3D immersion so vital for a successful short story.

‘Getting It Wrong’ by the doyen of British horror, Ramsey Campbell, is a riff on loneliness and social-intellectual decay, represented by superficial, manipulative TV game shows. Eric Edgeworth knows a lot about films but has no friends, so he’s dubious when called as a phone-a-friend film expert by a work colleague. When he refuses to take the game seriously and answers questions wrongly the consequences for her – and, ultimately, for him – are serious, and painful. Campbell aims a comic sideswipe at some pet hates, but his paddle is just too broad. The dark humour never quite hits the mark and the author seems to be getting more out of it than the reader.

Having read impressive work by Lisa Tuttle, ‘The Man in the Ditch’ is surprisingly weak; a pedestrian, meandering and, yes, predictable story in which a young wife’s vision of a body in a ditch near her new Norfolk home turns into a self-fulfilling prophecy. The stage is set, characters are introduced, ingredients are mixed in the bowl and placed in the oven, but the cake fails to rise as the ending looms as large as a skyscraper on the flatlands.

With this kind of cast there will always be inevitable highs, and the best stories weave some real dark magic. Two in particular shine like diamonds: Robert Shearman’s ‘Alice Through the Plastic Sheet’ and ‘A Child’s Problem’ by Reggie Oliver, which uses every paragraph of its 55 pages to paint a rich, colourful picture of a young boy’s ordeal and steep learning curve when he’s sent to live at his rich, tyrannical uncle’s large country mansion. The inspiration behind the story is an 1857 painting by Richard Dadd, and the narrative is Oliver’s imaginative response to the subject and atmosphere of the picture. This classic ghost story in the M.R. James mould – fortunately devoid of James’ characteristic bombast – creates a memorable evocation of period and place through vivid visual description, excellent characterisation and high quality writing. Nothing jars the reader out of this note-perfect story and one is eager to discover the horrors that George’s uncle has in store for him, George’s ability to fulfil his set tasks, and the purpose of the shades who appear in the grounds and seem to hold the key to unlocking his uncle’s darkest secrets.

Shearman’s gem supplies surreality and ingenuity in equal measure. ‘Alice Through the Plastic Sheet’ displays an obvious Carrollian influence, but is never content to follow the white rabbit and the story’s crazy mystique is kept intact and spiralling throughout its 40-odd pages. This suburban psychodrama plays like a low-budget, weird, unhinged film by a maverick indie director whose drug habit is getting out of control, but the final product is all the better for this. It’s chock-full of bizarre yet somehow resonant situations and remarkable imagery – the family dog puking itself into a plastic dog-facsimile and voyeuristic glimpses of sexually desirable dummies are particularly memorable. There’s a strong undercurrent of urban paranoia, working on our subconscious curiosities about ourselves and our place in the world, familiarities and boredoms of family life, the changes wrought when awkward new neighbours arrive (in this case unseen, creepy awkward new neighbours), and our fears of just how shallow the construct of individual and social reality really is. That these worries take on both physical and metaphysical form is testament to the multiple layers of the narrative, which attains postmodern levels of irony yet at the same time conjures a wistful 1950s period bleed-through. The vibe is like Carnival of Souls in deserted De Chirico plazas, as written by Philip K. Dick, and the piece hums with a deliciously disturbing vitality so expertly crafted that upon finishing it one is motivated to seek out other Shearman material in the hope of chasing the dragon.

The ‘second level’ stories – solid works that offer much without quite achieving Shearman and Oliver’s heady heights – form the majority of the pieces on show. John Ajvide Lindqvist’s ‘The Music of Bengt Karlsson, Murderer’ takes us back to his familiar rural Swedish settings. A young widower trying to persuade his 11 year-old son to play fewer computer games and appreciate culture more, bribes him to take piano lessons. When Robin begins playing a literally haunted melody and talking to unseen visitors in his room, his father unearths the chilling legacy of the house in the woods he was able to buy cheap, and does so the hard way. Loss, madness, child murder, haunted houses, the past refusing to stay dead – all present and very well done as one would expect, if not fully correct. There’s a lack of spark compared to the best of Lindqvist’s short fiction and the first person narrative voice may not have been the most effective way of framing the story, especially at the climax.

Peter Crowther’s ‘Ghosts With Teeth’ builds a deliriously paranoid atmosphere, using the pathetic fallacy of a biblical rainstorm in a cutoff township to underscore a modern invasion of bodysnatchers; there’s even a knowing dialogue reference to pods under beds. But these snatchers are ghosts, they are legion and they have teeth. The dialogue is excellent throughout, the burn is controlled and suspenseful, but then the thing just keeps on going and going and going, and the burn fizzles into repetition… it could be a lot tighter if shorn of maybe a quarter of its length, including its redundant prologue. Radio broadcasts discussing poltergeist activity and manifestations are unsubtle devices, overfamiliar from many low budget horror flicks. There’s a terrific story in here, no doubt, and while it is enjoyable for sure, at this length the piece winds the core ideas beyond their capacity to keep delivering shocks.

‘Near Zennor’ by Elizabeth Hand is perhaps the nearest pretender to excellence, but as a 66 page novella it’s the prime candidate for more judicious editing (anyone see a pattern here?). The narrative centres around another widower, an American architect named Jeffrey, who discovers old letters written by his English wife at age 13, and tries to divine the true nature of her youthful visit with two friends to a reclusive author of dark fantasy. The emotional thrust shifts from suspicions of a possible paedophilic encounter to dripping supernatural dread, just as the location shifts from New Canaan, Connecticut to the wilds of Padwithiel in Cornwall. There is much portentousness when Jeffrey arrives in England and interrogates his wife’s friend about what happened when they went to Cornwall together, but at 14 pages this section is too long and the backstory seems in danger of taking over. Later, when Jeffrey sets off to locate the writer’s remote farmhouse and perhaps find the answer to an historic mystery, the atmosphere ramps up and the reader is transported into the ancient and mysterious Cornish landscape. Rich use is made of olden terms like fogou, cromlech, tumuli and cairn, and other genre tropes are deployed to good effect – namedropping DH Lawrence and Aleister Crowley as near-neighbours; distorted time perception; no phone signal; punishing sunlight; unruly, disorienting topography that does not conform to maps. The fact that Jeffrey’s fumbling explorations occur at least twice however, over another 15 pages, dilutes the delightful frisson of fear delivered so well towards the end. There is also a final, fanciful twist – but it’s one helluva coincidence, and one that any screenwriter worth their salt would have seen coming as soon as a specific object makes an early appearance. Several genre authors have singled out this story for praise and it is a luxuriant dark piece full of foreboding and potential, but frustratingly overlong and repetitive if one judges it against the editor’s claims.

‘Roots and All’ by Brian Hodge concerns cousins Dylan and Gina’s attempt to unpick the mystery of Dylan’s sister Shae’s disappearance from their Grandma’s isolated house. More swings and roundabouts – well written and an interesting premise but with limited impact and a heavy handed subtext about social and environmental decline – this is workmanlike and kinda satisfactory without ever really gripping as tight or hitting as hard as it ought to.

Michael Marshall Smith rarely disappoints, and his ‘Sad, Dark Thing’ is a memorable, if slight, offering with a nicely transgressive and wistful air. Businessman Miller spends his Saturday afternoons driving aimlessly since his wife and daughter left, and one day he finds himself on a farm at the end of a dirt track paying a hick a dollar to view a sad, dark thing locked away in a hut. The thing is shadowy, insubstantial, beyond comprehension – but at the same time Miller intuits that it is female, and naked. Once he has purchased the thing and brought it home he finds it a natural process to take the encounter to the next level, but this level is not the one he had anticipated…

‘Last Words’ by Richard Christian Matheson, is hardly a fitting final piece in anything except title. It’s nasty all right, but also obvious, superficial and mercifully short.

So there it is. A Book of Horrors. What it says on the tin, more or less, but too many below-par efforts, too many pieces bursting at the seams, a few very creditable entries and two flat-out winners do not support the extravagant claims made on its behalf by its editor. That said, it would be churlish not to acknowledge the likelihood that die hard genre fans may get something more from the anthology, and they might even agree with Jones’ assertion that it contains a superior brand of horror story. That’s the beauty of subjectivity you see, and there is enough of interest here to at least entertain the possibility.

JOHN COSTELLO

Extra Info

Publisher: Jo Fletcher/St. Martin’s Press

Paperback (400pp)

If you enjoyed our review and want to read A Book Of Horrors please consider clicking through to our Amazon Affiliate links. If you do you’ll help keep the This Is Horror ship afloat with some very welcome remuneration.

2 comments

Thank you! Yes!

Given what was said in the book’s prologue, “what happened to horror” is that it needed a buttload of editing and for something to happen.

I can’t wait to read A Book Of Horrors. Lex Sinclair author of (Neighbourhood Watch, Killer Spiders and Nobody Goes There).