The novella is one of those literary forms that I have admired for a long time – a quicker read than a novel but a fuller experience than a short story. In the mainstream publishing world, it appears to be something of a neglected format (although, having said that, in a relatively recent visit to a well-known chain bookstore, I did see a few slim books out on display in the Fiction section which I suppose could be classed as novellas and, as described below, quite a few ‘classics’ were written as such), with the probable major publisher excuse that ‘it doesn’t sell very well’, or ‘there isn’t much interest’ as to why they’re not more widespread, the same explanation for why short story anthologies and collections are but very rarely forthcoming from the big imprints. And yet, this is despite a very healthy market for both forms within genre – perhaps, even though genre probably accounts for a large slice of the bookseller’s market, the numbers in the round don’t warrant publishers taking any risks.

The novella is one of those literary forms that I have admired for a long time – a quicker read than a novel but a fuller experience than a short story. In the mainstream publishing world, it appears to be something of a neglected format (although, having said that, in a relatively recent visit to a well-known chain bookstore, I did see a few slim books out on display in the Fiction section which I suppose could be classed as novellas and, as described below, quite a few ‘classics’ were written as such), with the probable major publisher excuse that ‘it doesn’t sell very well’, or ‘there isn’t much interest’ as to why they’re not more widespread, the same explanation for why short story anthologies and collections are but very rarely forthcoming from the big imprints. And yet, this is despite a very healthy market for both forms within genre – perhaps, even though genre probably accounts for a large slice of the bookseller’s market, the numbers in the round don’t warrant publishers taking any risks.

And, of course, it’s easy for me to say sales of short stories (in my case, chapbooks) and novellas are healthy, considering that I only print one hundred at a time (although I can foresee that changing at some point). Needless to say, they go pretty fast and very rarely, if ever, am I left with any surplus. However, turning things on their head, the fact that I still get people asking me if there are any copies left after I’ve sold out of a particular title indicates that the interest is indeed there – I am fairly sure that should publishers ever go into that niche they may find themselves a tad surprised at the response.

Exploring the best horror novellas

One of my favourite novellas is Clive Barker’s 1986 The Hellbound Heart, the story which launched the Hellraiser film franchise. (Interesting fact – Pinhead is never mentioned by name in the book and he’s not the leader of the Cenobites either – that only came later in the film.) But the novella itself has an extremely distinguished pedigree, with writers as diverse as Kafka, Steinbeck, Orwell and Conrad utilising the form. In terms of the ghost story, my own area of expertise, one of the most well-known is Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, wherein the ghost of Jacob Marley visits the miserly and uncompassionate Ebenezer Scrooge to advise him to change his ways or else. Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw, a masterpiece of chilling atmospherics, is another example of the form. Here, a governess charged with looking after two young orphan children comes to the belief that some spiritually unhealthy forces are stalking them.

Horror of a different kind is the central theme of Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange. Here it’s not just the terror of the social breakdown as evidenced by the nocturnal shenanigans of the gangs of droogs, brutal thugs preying on those unlucky enough to have been caught outside during the hours of darkness, but whose sole purpose in life appears to be the exercise of ultraviolence. When the authorities experiment in the redemption of the main character, Alex, we are left with the unsettling question of which is the greater evil. A variation on the theme pertains in George Orwell’s Animal Farm, a satire on the Russian Revolution using farm animals as metaphors and cyphers. The central point being made in this one is that, even with the best intentions, human nature being what it is will always revert to the way things were before.

A couple of others worth mentioning, before moving on – first, what is probably the only vampire story I actually like which also happens to straddle the novella/novel border: I Am Legend by Richard Matheson, the tale of the last human being left on earth, Robert Neville, after civilisation has collapsed and everyone else has been turned into a vampire. Hunting them by day, he becomes the hunted himself at night when the creatures are at their strongest. It’s a thought-provoking piece: what would YOU do in such a situation – would you struggle to survive as Neville continuously does, or would you just give in to the inevitable?

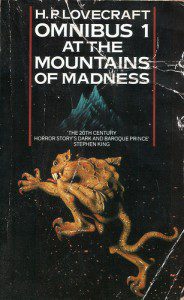

The other classic novella I wanted to mention here is HP Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness. Not only is it a marvellously chilling story of an Antarctic expedition finding something that shouldn’t be there (namely the ruins of a vast unknown city and the remains of ancient, unidentifiable life-forms, which are neither plant nor animal) but it was also my first ever encounter with the work of the providence scholar. Needless to say, within the course of reading this novella, I became hooked on the man’s work and have been reading it ever since.

The other classic novella I wanted to mention here is HP Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness. Not only is it a marvellously chilling story of an Antarctic expedition finding something that shouldn’t be there (namely the ruins of a vast unknown city and the remains of ancient, unidentifiable life-forms, which are neither plant nor animal) but it was also my first ever encounter with the work of the providence scholar. Needless to say, within the course of reading this novella, I became hooked on the man’s work and have been reading it ever since.

So, you may legitimately ask, why am I going on about novellas and what connection do they have with anything? Is that man Marshall-Jones finally running out of things to say here and is therefore just waffling off the top of his head to fill the required space?

Well, no, there is actually a point to all this. Astute readers of this column will know that I run Spectral Press, which has primarily been known for its championing of the chapbook, another lamentably ignored literary form. This year, I also launched a series called Spectral Visions, which concentrates solely on the novella format. So far, two have been published, namely Gary Fry’s The Respectable Face of Tyranny and John Llewellyn Probert’s gloriously gruesome romp The Nine Deaths of Dr. Valentine. In 2013 there will be another two issued, written by two heavyweights of the genre, who also happen to be Welsh and bald just like me – Stephen Volk and Tim Lebbon.

Stephen’s novella Whitstable (May 2013) is already garnering superb plaudits from those who have been lucky enough to read the manuscript, and I can honestly say that it’s amongst the best pieces of writing I have ever read. I may be biased, but it is indeed a tour de force, absolutely gripping from beginning to end. There are no supernatural elements anywhere in the book: however, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t any monsters – the modern evil he fights is very real. Anyway, for all horror aficionados both the author and the place name should be familiar: Stephen was the man behind the highly successful and controversial Ghostwatch drama screened at Halloween in 1992 and Whitstable was, of course, where the late great actor Peter Cushing lived until his death in 1994. The date is also significant, as the actor was born in May 1913 – and the book is being published to coincide with the centenary of Cushing’s birth.

As for Tim Lebbon’s novella, that is as yet untitled – however, I can tell you the two novellas of his which inspired me to approach him to see if he was interested in writing something for me – The Thief of Broken Toys (published by ChiZine) and Nothing Heavenly, which appeared in Cemetery Dance’s collection of the author’s short stories, Last Exit for the Lost. The former is a lyrically-told tale of a father, Ray, who loses his son and whose wife then leaves him, pitching him into a deep hole of grief, loss and despair. He meets a man who promises to fix all of Ray’s son’s broken toys that he’d promised to mend when his son was alive, but never got around to. What follows is one of the most heartbreaking and heart-rending explorations of unfathomable grief and loss, a truly beautifully written tale. Nothing Heavenly is a story based around the war between Heaven and Hell, and a young woman who is imprisoned by forces she cannot understand and for reasons she cannot discern. She has to find out which side it is, Heaven or Hell, which is keeping her against her will and why… It’s a widely-sweeping, marvellously imagined and cinematic story that, after I read it, I could easily imagine being translated to the big screen. I would go further than that and state that it demands such treatment. I suggest you track down a copy of this collection forthwith – it showcases a writer at the top of his game and most inventive, and you won’t regret buying it for one second, I can guarantee.

Why read novellas?

To finish, then, I’ll leave you with a brief explanation as to why I particularly like novellas. Many of you out there know that I am a very busy man, what with all the editing, publishing and column writing I do. I also love to read, so while short stories fill the gap amply enough, there are times when something a little more substantial is needed. I very rarely get the time these days to start and finish a novel, so something in between is perfect – and that’s where the novella comes in. Each form has its merits, but a writer is able to develop themes and characters better in a novella than a short story, conversely the story still has to be as focused as that of a short story. I sometimes find that novels, by their nature and size, mean that the plot becomes blurry and lost over the course of its length; there are very few modern horror novels that manage to significantly grab me and hold me (Adam Nevill’s The Ritual is one such example that comes highly recommended). Novellas, then, fulfil the criteria quite nicely in this respect.

For me then, it’s more than just a commercial decision, a lot more than that, in fact. I love the format, and my ambition is to push the novella forward a bit more into the book-buying public’s consciousness, and make it as special and desirable as any literary object. The novella deserves as much of a place (as well as respect) as any other format of literature on anyone’s bookshelf. Whether it’s a classic piece of writing or a ghostly tale, please join with me in exploring the beauty of the novella.

SIMON MARSHALL-JONES

3 comments

Great piece and I whole-heartedly agree with you.

Some cracking horror novellas I’ve read recently include Cate Gardner’s Theatre Of Curious Acts, Mark West’s The Mill and What Gets Left Behind, and Robert Dunbar’s Wood.

I’m sure there’s many, many more.

Laird Barron has some works of the novella length, and all brilliant. Best horror author currently writing.

Hooray for the novella and hooray for the short story! I think both genres are overlooked and underestimated by too many folk, so I’m very happy to see the crafts being celebrated here. Some plank described my short story writing recently as me ‘working up to writing a novel’. How I kept my temper I don’t know…