St. Valentine’s Day is nearly upon us once again, when thoughts turn to love and our nearest and dearest. A day that is bound up with and representative of all that is deemed the epitome of romantic; hearts and flowers, candlelit dinners, kisses and nights between silken sheets. However, look into the history of the shadowy figure of St. Valentine himself, and it’s anything but romantic.

St. Valentine’s Day is nearly upon us once again, when thoughts turn to love and our nearest and dearest. A day that is bound up with and representative of all that is deemed the epitome of romantic; hearts and flowers, candlelit dinners, kisses and nights between silken sheets. However, look into the history of the shadowy figure of St. Valentine himself, and it’s anything but romantic.

St. Valentine (or Valentinus in Latin), may not even have been a single person, but an amalgamation of several similarly-named individuals. What we do know is that there are more than a few martyrologies associated with the name, which are mostly unreliable, but legend has it that St. Valentine was killed on the Via Flaminia in Rome sometime in the third century AD for his beliefs, presumably around 14February. He isn’t officially recognised by the Catholic Church as worthy of veneration, but the Eastern Orthodox tradition celebrates two of them (hence the problem of attribution): St. Valentine the Presbyter on July 6 and Hieromartyr St. Valentine on July 30.

So how is it that this relatively obscure saint came to be so inextricably connected to the day of romantic love that people celebrate every year? It appears that Geoffrey Chaucer was the first writer in English literature, in Parliament of Foules, to make the connection, and that eighteenth century antiquarians such as Alban Butler (in his Butler’s Lives of the Saints) and Francis Douce then embroidered the connection even further, their suppositions weaving themselves into the mass of today’s social consciousness. Much of what these two learned gentlemen promulgated has been disputed in academic circles recently but, despite the grumblings, the upshot is that the saint is now forever linked to cherubs shooting arrows through hearts. From a bloody martyrdom to the patron saint of love – quite a trip!

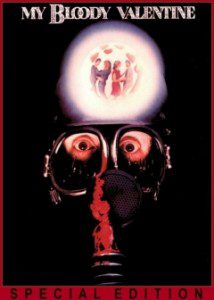

The link between St. Valentine and violent death was reinforced one day in 1929, when seven mob bosses were summarily gunned down in Chicago, the result of a gangland conflict between Al Capone’s South Side Italians and Bugs Moran’s North Side Irish outfit. In popular film media, the connection is often made even more explicit, what with maniacal stalkers and unhinged slaughterers single-mindedly pursuing the objects of their slightly warped lusts in a way guaranteed not to land them a second date. Look to films like My Bloody Valentine (1981 & remake 2009), Lover’s Lane (1999) and Valentine (2001) for celebration-day specific horrors.

Love is also inextricably bound up with two other things: sex and beauty. Sex, of course, is in many ways the force driving mankind forward, the ever-present primal instinct for species-preservation writ large. In addition, the orgasm has often been characterised as ‘la petit mort’ – the little death. Beauty, on the other hand, is a quality which is considerably less tangible and difficult to grasp. It’s elastic, its meaning changing from person to person, which is qualified even further with small matters of personal taste, upbringing and outside influences. Everyone sees beauty differently, but even so there are widely accepted reference points as to what is generally conceived as ‘beautiful’, especially encapsulated in those concepts espoused by the mainstream media – in the case of women, for instance, flawless skin, slender bodies, perfectly proportioned features, attractive eyes and teeth, and a radiant smile. Scars and imperfections are seen as anathema, as blots upon the copybook. The traits of the beautiful people are given to us as guidelines to be observed, rewarding those who follow them and punishing those who step outside those bounds.

Yet, there are others who see things considerably differently. In this respect and in relation to the horror genre, I once again turn to my favourite writer and director as the prime example of someone who wishes us to break out of the narrow confines of imposed rules and regulations: Clive Barker. The two examples I am thinking of in particular are, of course, his most famous creations – the worlds of Hellraiser and Nightbreed. Both of these exhibit extremes in definitions of the grotesquely beautiful, especially in the case of the latter. Nevertheless, those of us who look beyond the mere superficial realities are inspired to marvel at the admittedly warped perfection of nature the Cenobites and ’Breed represent. This is contrasted against the background of the portrayal of human nature, which is often seen as brutally ugly (Julia in Hellraiser and Dekker and the official authorities in Nightbreed).

Both sides are acting out their natures for all to see but there is a subtle difference between the two at play here. In both Julia and Dekker, the ugliness they conceal is carefully hidden behind a veneer of respectability; a stage-managed and superficial gloss of the norms expected of us by society. With both the Cenobites and those who belong to the Nightbreed what you see is what you get. Moreover, they are intensely proud of their respective natures, and aren’t afraid to show it, even if in the case of the latter they can only show it amongst themselves after having been forced underground, away from the aggressiveness of humans.

At the root of all these actions is another aspect of love – desire. Julia desires the feral Frank in opposition to the insipidity of his brother Larry (and of course Frank himself desires the ultimate experience, which in turn precipitates all of the following situations), and Dekker desires to hide his predilection for torturing and killing from the authorities by blaming it on a hapless victim i.e. Boone. It’s also a desire to absolve himself from responsibility for his actions, hence why he hides his murderous penchant behind a mask. Boone himself is also subject to desire: one which seeks to discover the truth as well as a place to belong. Furthermore, the ’Breed themselves only wish to be accepted for who they are, and to remain unmolested so they can live out their lives in peace.

The Cenobites are, in terms of controlling desires, more problematic insofar as whatever motivates them is so beyond what can be accepted as normal parameters. Here, I would aver that the desire to perfect their arts of exploring the boundaries of what constitutes the ultimate in pain and pleasure is the driving force. This is a requisite part of their innate characteristics, and is as much a constituent of them as art and literature are of civilised culture. Take those aspects away and you would essentially redefine and emasculate them. The same is true if somehow art and literature vanished overnight from civilisation. Moreover, one could say, albeit tenuously perhaps, that the Cenobites ‘love’ what they do. To them, violence is both balletic and poetic, the ultimate expression of their definition of love.

Imperfections, too, are highly celebrated in these individuals – scars are the markers of difference, of a life lived outside the confines of normal existence, and worn with pride as the demarcation between mainstream and non-mainstream. It is what makes them distinct from others, gives them a solid individuality, and defines them physically and mentally. There’s no hiding behind a false perfection, they are who they are and you can either take it or leave it.

So, what drives the enemies of difference? Simply, it is fear: fear of the unknown, fear of what is not immediately comprehensible, or what is seen as ‘abnormal’. People, in real-life as in fiction, live within certain parameters that have been defined by others and which they’ve been told ‘is the only way to be/live’ so anything which ‘threatens’ that is seen as a menace. It is easier to eliminate than it is to seek understanding. What Barker is essentially saying is that difference should be embraced, not excluded – after all, it is the maverick personalities who get things done and move humanity forward, not those who cocoon themselves away in concepts which are steadily and inexorably dating.

You know, it’s true what they say: it isn’t the monsters which are ugly, it’s the humans.

SIMON MARSHALL-JONES