So, the season of goodwill and peace to all mankind is nearly upon us. Let us conjure up in our minds a typical vision of Christmas, the one that we’re all meant to aspire to or the one that we’ve been sold over the years, depending on which outlook you cleave to. It usually goes something like this:

So, the season of goodwill and peace to all mankind is nearly upon us. Let us conjure up in our minds a typical vision of Christmas, the one that we’re all meant to aspire to or the one that we’ve been sold over the years, depending on which outlook you cleave to. It usually goes something like this:

Christmas Eve: a cosy room in a brightly lit house, a roaring log-fire blazing in the grate, cards from friends and family lining the mantelpiece, tinsel and paper-chains hanging from the ceiling and, standing guard in a corner, a tall fir tree festooned with baubles and lights, with colourfully-wrapped parcels strewn beneath its branches. Outside, snow is falling gently, turning everything into an unfamiliar wonderland. Lantern-lit carol-singers are outside the door, bringing even more cheer and heralding the arrival of the day itself; their voices lifting gloriously through the cold night air. Indoors, where it’s blissfully warm, adults are hurriedly attempting to herd excited children up to bed, with the promise that Santa will visit them during the night while they’re asleep, but only if they’re good.

Once the little ones are safely tucked up, the adults retire to the living room, where warming glasses of port are handed round while one of their number, standing by the fireplace, puts forward a suggestion that everyone should tell a ghostly story to fill the time before going to bed. And so, each of them take their turn in trying to out-scare the others…

If we go back a century or more, this is exactly the kind of scene being played out in households up and down the country. (Okay, I recognise that only the better off would be able to do such things, but please bear with me.) The telling of ghostly tales was a favoured pastime of the Victorians in particular. This, then, begs the question: why did people tell each other ghost stories on the night before one of the most joyous occasions in the yearly calendar?

The roots of the Victorian Christmas were, in many ways, pagan – albeit wrapped in the trappings of Christianity. Many of the traditions we have come to associate with the season were introduced by Queen Victoria’s consort, Prince Albert, importing them from his native Germany. Despite the Chistianising of western countries, much of the lore and practise of their ancestors survived as an undercurrent beneath daily life, especially in the rural areas. Of course, it wasn’t limited to country-folk – as noted above, aristocracy also embraced many of its echoes, albeit in much-diluted form. Historically, pagan belief in the Otherworld was part and parcel of ritual and daily life for such ancestral societies – grave goods interred with pagan burials attest to the strength of the connection between the world of the living and that of the dead. Furthermore, it appears that communication was two-way, one influencing the other. Tie all this into the idea that mid-winter day, containing as it does the longest night of the year, was the time when the souls of the dead were at their closest to the earthly realm (Halloween wasn’t celebrated then in the way we do now), it was the ideal opportunity for two things to occur: firstly, the dead were abroad in the freezing moonlit night, meaning that being safely ensconced with your loved ones indoors was especially to be desired and, secondly, Christmas was a time to remember those long departed. In other words, despite the passage of long millennia, the beliefs and ‘philosophy’ of those long-gone forebears survived into the civilised age. The Victorians merely adapted them to their own needs. The telling of ghost stories in their parlours at Yuletide, then, could be seen as both entertainment and as an act of remembrance.

We must also recall that fin de siècle Victorian society was quite heavily immersed in the occult, what with intense interest in spiritualism, séances, Theosophy, magic and Hermeticism (most famously incarnated as the Society of The Golden Dawn, which spawned the infamous bête noir Aleister Crowley), as well as Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism, entering the parlours of all the fashionable circles. Is it any wonder, then, that ghost stories and tales of the Otherworld gained such popularity?

The likes of Charles Dickens and MR James wrote spooky stories specifically for Christmas. In fact, it was how the latter started his writing career. He would write little tales to entertain people at his lodgings at King’s College, Cambridge on Christmas Eve, which then became a regular custom in all his years there. During the halcyon days of the ghost story as we’ve come to think of it, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, annuals of these scary seasonal tales were issued every year. Established periodicals often included a ghostly tale or two in their Christmas number. As might be surmised, it became something of a publishing tradition.

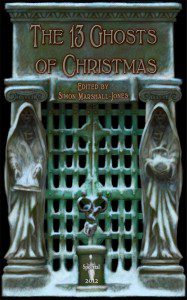

So, what’s the foregoing cultural and historical preamble above in aid of, you might ask? The answer is simple: Spectral Press is going to attempt to revive the tradition of the Christmas Ghost Story Annual, beginning this December with the publication of The 13 Ghosts of Christmas 2012. The idea originated, as these things so often do, from reading an off-hand remark on Twitter, when the writer Scott Harrison lamented out loud about the demise of this species of collection. My neurons started firing instantly, and so were planted the seeds of the idea of the anthology. Submissions started flowing in early in January this year and by the passing of the deadline I’d received over seventy stories hopeful of inclusion. Without a doubt, the standard was consistently high, making the winnowing of the number down to just thirteen that much more difficult. After a lot of umming and ahing I finally did it – however, there was also a distinctly happy upside: I have enough stories for next year’s annual too, the quality was that good.

The annual will contain not only well-known names like Gary McMahon, Paul Finch, William Meikle, Raven Dane and Adrian Tchaikovsky, but also standing proudly alongside them will be lesser-known names such as Thana Niveau, Jan Edwards, Neil Williams and John Forth. There will also be contributions from new writers such as Martin Roberts, Richard Farren Barber, Nicholas Martin and John Costello. In other words, there will be a wide spectrum of ideas and interpretations to choose from – there’ll be something to cater for all tastes within its pages.

The hardback edition will also contain a bonus story, not available in the paperback: a preview of the next Spectral Visions novella, Whitstable, from TV and film screenwriter Stephen Volk (Ghostwatch [which is celebrating its twentieth anniversary this year], Afterlife and The Guardian [directed by William Friedkin]). The novella will be published in May 2013, to mark the centenary of the birth of Peter Cushing, one of Britain’s finest actors and a marvellous human being. He’s the main protagonist of the tale, confronting a real-life horror far scarier than any monster he was asked to deal with onscreen. More details on that coming soon!

In the meantime, visit Spectral Press for more information on the annual itself and how you can pre-order – but hurry, copies are already going fast!

SIMON MARSHALL-JONES