In her introduction to Australis Imaginarium (2010), Tehani Wessely succinctly summarises an idea that has become something of a truism when it comes to discussing horror and dark fantasy stories with Australian settings:

There’s simply something about the vastness of this land and the many weird, wild and dangerous creatures that populate it that lends itself to terrifying tales.

Looking at Australian short fiction published in recent years, we can see exactly what Wessely means. These stories are riddled with manifestations of ‘Australian Gothic’. Many of them depict rural isolation: people alone in the desert, in the bush, by the sea. Underlining human and supernatural threats is nature itself, harsh and unforgiving; over it all hangs an endless, suffocating sky. The settings in these narratives are more than just unsettling or uncanny; there’s an unheimlich quality to this country’s wilderness, which makes it clear that most characters – human or otherwise – are unwelcome. Leave, they seem to say. You don’t belong here.

Looking at Australian short fiction published in recent years, we can see exactly what Wessely means. These stories are riddled with manifestations of ‘Australian Gothic’. Many of them depict rural isolation: people alone in the desert, in the bush, by the sea. Underlining human and supernatural threats is nature itself, harsh and unforgiving; over it all hangs an endless, suffocating sky. The settings in these narratives are more than just unsettling or uncanny; there’s an unheimlich quality to this country’s wilderness, which makes it clear that most characters – human or otherwise – are unwelcome. Leave, they seem to say. You don’t belong here.

When we think of Gothic literature – Australian or otherwise – several themes or features immediately come to mind: ghosts from the past (literal and metaphorical) rising up to oppress the stories’ protagonists; a sense of discomfort, of being unwholesome, resulting from breaking social taboos; overwhelming darkness, hopelessness, claustrophobia, and disintegration. Australia’s colonial/convict history is an obvious source of inspiration for this type of horror – but there are so many Australian Gothic stories set in the colonial period that we’ll have to save discussing them for another time. Instead, I want to focus on stories that feature ‘the vastness of this land’ – either as a backdrop to dark short stories, or as a fundamental part of the horror itself.

In Sue Isle’s ‘The Painted Girl’ (Nightsiders), we get the impression that nature is obliterating the past as well as shaping the present. Bushfires rage in this story’s opening, ravaging the landscape and making it indistinguishable from Australia as we currently know it. At the same time, fire is a controlling force: it shepherds the characters, driving them inward, making them run. Bushfires function in a similar way in my story ‘White and Red in the Black’ (Dead Red Heart); burning-earth fences the characters in, keeping them contained, terrified within the confines of their homestead.In Paul Haines’ ‘The Past is a Bridge Best Left Burnt’ (The Last Days of Kali Yuga), we don’t see the fire itself, but its smoke. Like a bell jar descending on the city, a grey pall echoes the protagonist’s increasingly dark thoughts, enhancing the sense that he’s being stifled, suffocating in his life.

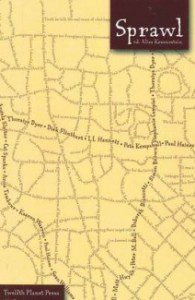

Drought, like fire, often turns the land to dust in these Australian stories, obliterating the past and making the future look bleak. After offering glimpses of scorched, otherworldly trees and black earth, the final lines of Sean William’s poem ‘Parched’ (Sprawl) are a haunting refrain, and a promise of worse to come: “it never rains / for long / here.” And in ‘Virgin Jackson’ (Australis Imaginarium) Marianne de Pierres takes us to an inhospitable, not-so-distant time in the future, where hot north-east winds “evaporated the fluid from your body in seconds” and “scoured the wayback into grotesque landforms, sharp gullies and dust ball plains.” Images of dusty, desert (and deserted) plains feature most prominently in these short stories: often cast in shades of sunset, representations of the country’s red heart seem to be used as shorthand for the wide open fear of the Australian landscape.

Drought, like fire, often turns the land to dust in these Australian stories, obliterating the past and making the future look bleak. After offering glimpses of scorched, otherworldly trees and black earth, the final lines of Sean William’s poem ‘Parched’ (Sprawl) are a haunting refrain, and a promise of worse to come: “it never rains / for long / here.” And in ‘Virgin Jackson’ (Australis Imaginarium) Marianne de Pierres takes us to an inhospitable, not-so-distant time in the future, where hot north-east winds “evaporated the fluid from your body in seconds” and “scoured the wayback into grotesque landforms, sharp gullies and dust ball plains.” Images of dusty, desert (and deserted) plains feature most prominently in these short stories: often cast in shades of sunset, representations of the country’s red heart seem to be used as shorthand for the wide open fear of the Australian landscape.

The dangers inherent in the desert are usually referred to within the first few pages – and often in the first paragraph – of these tales. Not just to set the scene; these descriptions instantly add a horrific tone to each piece, to suggest that things can only get worse in what’s to follow. For example, Jason Fischer opens ‘Undead Camels Ate Their Flesh’ (Dreaming Again) like so:

With its usual efficiency, the sun blazed down on bugger-all. It was the Outback, with nothing for hundreds of miles but heat, dust and flies.

This offers a bleak, uncompromising picture of Australia, much like the first lines of Joanna Fay’s ‘Black Heart’ (Dead Red Heart):

It was time to die. That was why she’d come here, to the red land. The sky swept over here, horizon to horizon, uncompromising scarlet. The colour of her unlife, like the sands stretched wide to meet it.

Likewise, Dirk Strasser’s ‘The Dark Under the Sun’ (Australis Imaginarium) captures the feeling that this is not a place where life thrives:

There was red flatness as far as he could see, like a fire that had been trampled to death by a thousand feet, but which had somehow managed to keep its heat while its flames had been killed. Out of the heat grew clumps of grass and twisted, black-bodied trees, but they were so few and far between that it was as if rather than being in the process of living, they were in the process of dying.

Even when the stories take place after dark, the sun, the desert and its denizens are treated as pervasive, immediate concerns. Though sunset brings with it cooler temperatures, in ‘Sun Falls’ (Dead Red Heart) Angela Slatter reminds us of “the sounds of the night: cicadas, possums, snakes, lizards, hares, wallabies. All manner of nasties that don’t come out in the sunlight.” While Slatter’s story cuts with black humour, Alan Baxter’s ‘Punishment of the Sun’ (Dead Red Heart) adds a more melancholy edge to the land after sunset. Baxter describes a “world beyond stygian and dead” with “dry, dusty paddocks with dry, dusty horses, ribs like xylophone keys through thin, scabby hides. The orange desolation dragged on as far as hope would last in every direction. Too young to leave this desiccated hole, [Annie] grudgingly endured.” This notion of Australia as a ‘Hell’ or a ‘hole’ to be endured is also present in the opening paragraph of Pete Kempshall’s ‘Signature Walk’ (Sprawl), in which a little girl asks:

‘Where’s Australia, Granddad?’ … He held her gaze and pointed straight down at the ground. She shook her head. ‘No, Granddad, you’re wrong … Australia can’t be down there,’ said the girl with absolute assurance. ‘That’s where Hell is.’

Marty Young also draws on hellish imagery to set the ‘horror’ tone of his story, ‘Desert Blood’ (Dead Red Heart):

The world began to bleed as the sun melted into the horizon. Hell was leaking, its blood seeping up from the sand and the sunset itself to reflect in the slow moving Cooper Creek next to them.

The sun setting over expanses of red sand lends itself to plenty of lovely Gothic imagery: crumbling buildings in silhouette, darkness limned with blood and crimson wastelands. However, the Australian sky is perhaps at its most frightening, its most suffocating, during daylight hours. “The sky was blue as a vein the day I killed my father,” begins Stephen M Irwin’s ‘Hive’ (Macabre), but it “wouldn’t stay that way; the strange, ice-fire blue eventually gave way to eerie grey, then to the red of sick blood.” The sky’s disintegration from brightness to blood foreshadows the young protagonist’s psychological turmoil, his vivid dreams and descent into a sort of temporary madness. Moreover, it reflects Michael’s very personal horror. By contrast, the sky in Sean Williams’ ‘Passing the Bone’ (Australis Imaginarium) is “a blue sheet pressing down on the world” that seems designed to stifle everyone, like a pillow pressed over the face. The vastness of the Australian wilderness is contained only by leaves and sky in Margo Lanagan’s ‘Pig’s Whisper’ (Agog! Ripping Reads)

The bush was vast around them, immense above them; its frail roof of leaves was a sky within a sky.

Out here, the children are frightfully exposed; they are plunged into Australian lore, and must figure their own way out.

Two stories published in recent years are standouts, in my opinion, for integrating characters and their plights from the world in which they exist. The first is ‘Smoking, Waiting for the Dawn’ (Dreaming Again) by Jason Nahrung. This piece marks its territory by describing dusty red land, but where many of the examples I’ve given above use Australia’s unforgiving climate and its deserts as a backdrop to the action, this piece’s setting is integral in conveying the weariness, exhaustion, and wonderful bleakness that are driving forces in the plot:

George stood by the bleached skeleton of the Wyandra stockyards, breathing in dust and sun-baked silence. The rust-red roofs of the township shimmered in the heat haze, and from what he could see, his old stomping ground hadn’t fared much better than he had in the past twenty years: tired, forlorn, running out of time.

This is Australian Gothic. Hopelessness and the certainty of defeat right from the word go. A relentless sense of doom ingrained in the very dirt. And the characters forging on, regardless. A similar effect is achieved in Nahrung’s ‘Wraiths’ (Winds of Change); there is a feeling of not-quite-acceptance, a stoic weariness in the face of ‘natural’ threats, established right from the first paragraph:

The dust wraiths struck with all the speed and surprise and finality of a slamming door. We should’ve felt it coming, but we didn’t. Maybe it was the heat, dulling our senses with its touch of lazy. Maybe it was just our time and, on some level, down deep, we knew it and ignored the signs. Or maybe they’d just got tired of us and decided to end it, once and for all.

Heat, dust, sun and desert are embodied in Nahrung’s characterisations; these people are the landscape, and its chilling horrors, personified – you can practically hear red dust grinding between their teeth, in their bones – which makes this authors’ stories essential reading for anyone interested in Australian horror.

The second piece that shouldn’t be missed is Paul Haines’ ‘Burning from the Inside’ (The Last Days of Kali Yuga). Although this story is mostly set in Adelaide – it integrates city settings with the more iconic ‘sunburnt country’ imagery – it captures the spirit of Australian horror in an absolutely chilling way. In Haines’ fiction, setting is never a trope or a cheap add-on. And in this piece in particular, it’s impossible to separate the protagonist from his surroundings. From the first line, we’re given insight into his mindset, and how Adelaide has helped to shape it:

I’d like to say I feel unsettled here, but I don’t.

Right away, we learn that this setting is something we should be afraid of, something we should feel unsettled by. At the same time, this line immediately hooks us into the true point of the story: this city, this setting, can be unforgiving and scary, but it is the protagonist’s perception of Adelaide – and his being so at home in this place – that makes us shudder to the core.

From my hotel room I can see the river Torrens snaking through the park, the lush of leaf in contrast to the desert sands that lap at the shoreline this city makes. The sun is settling on the horizon, finally a thing of beauty rather than the raging father in the sky, now its urgency is almost spent. One can imagine the river, that gurgle of water, a searing temptation for the heat bursting forth from the dead heart of this red island continent. A thirst to be quenched? Or something to be destroyed, the last bastion of hope holding back the inevitable conquest that shapes this dry land? Ornate spires reach for the heavens, dozens of them, over trees, nestled between crossroads and office buildings, the cross of Christ thrust up bold and true. One only has to glance in any direction to find the house of God here. From this spot alone I spy the Holy Trinity, Scots, St Patrick’s, St Peter’s, Christ’s, Brougham Place and Immanuel. And here I am. In the City of Churches. Adelaide. My new home for the foreseeable future. The murder capital of Australia.

There are so many contrasts, so much tension in this paragraph alone: city/country, drought/drowning, heaven/hell, life/death, past/present; it is a complex and disturbing sketch of the city, and the land surrounding it. In this story, more than any other, the setting – with its deadly creatures, ruthless atmosphere and horrific history – possesses the main character. It haunts and inhabits him. It tears him apart even as it gives him purpose. It will not leave him alone.

This is Australian horror. And it is absolutely terrifying.

LISA L HANNETT

If you enjoyed Lisa L Hannett’s column, please consider clicking through to our Amazon Affiliate links and buying her fiction. If you do you’ll help keep the This Is Horror ship afloat with a very welcome slice of remuneration.

Buy Lisa L Hannett fiction (UK)

Buy Lisa L Hannett fiction (US)

4 comments

Skip to comment form

Great column, Lisa! It occurred to me that if you’re of a mind to travel to Tasmania you might be interested in this women in horror film festival, entering its second year…

http://strangerwithmyface.com/

That is a great column, and well researched Lisa!

But let me take this opportunity to position my brand of Australian fantasy in direct opposition to your Australian Gothic. Like Banjo Paterson in the Bulletin Debate of 1892-3, I say to all you budding Henry Lawsons that Australia is a welcoming land, a beautiful and exquisite land teeming with magic and miracles, and you can find that in my work a little more subtly than you can in Mr Paterson’s. Good day to you!

Thanks, Tansy! And what a cool event — I’m so sad I won’t be able to make it this time. Fingers crossed they run it again next year…

Did you ever go Lisa ??. Rather curious.