Today is the third in a series of columns by David Moody to mark the release of Autumn: Exodus, the final book in his acclaimed Autumn series. Moody has been writing about the end of the world for almost thirty years. His novel, Hater, was optioned for film by Guillermo del Toro.

Things have changed dramatically in the world of zombie fiction. When I began peddling undead stories, zombie fiction wasn’t even a recognised thing. As I’ve mentioned in previous columns, when I started out, I was one of a handful of authors writing in the field. Fast-forward twenty-odd years (and they have mostly been ‘odd’ years, it must be said) and things are very different.

Last time I was here I talked about how, early in the new century, there was an exponential rise in the volume of zombie books and films being produced. All too often storytellers themselves have been guilty of demonstrating zombie-like behaviour and following the pack, imitating successful approaches. Zombie mashups are a case in point. Back in 2010, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies became an enormous hit. A big-budget movie adaptation followed the novel, as did a huge number of sequels, prequels, and other ‘re-writes’ of classic novels (I particularly enjoyed The War of the Worlds with Zombies if I’m honest). The mashup trend then branched out to include other monsters (see Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters, Abraham Lincoln – Vampire Hunter etc), as well as many books where pop-culture collided with the living dead – Paul (as in McCartney) Is Undead and Night of the Living Trekkies to name but two.

The zombie genre has always been a place where good (and not so good) ideas have been readily reappropriated, spreading like a virus. There have been endless authorised and unauthorised sequels to classic movies, and plagiarism is regularly rife. Even the shoddy movie adaptation of my novel Autumn appeared variously re-labelled as The Dead Walking and Autumn of the Living Dead by rogue distributors in certain territories. Incidentally, the naming of books and films as something ‘…of the Dead’ or ‘…of the Living Dead’ has become a real pet hate of mine. It can be tiresome, don’t you think? It’s almost like the author/director is telling you to lower your expectations because they’re going to serve up something derivative and uninspired.

It’s all a bit disappointing, given how incredibly adaptable and malleable the undead are. So, the question is, in the face of a virtual tsunami of competition, how do you buck the trend and find an original zombie story to tell? How have some books and films managed to escape from the masses? I have thoughts …

I guess the first thing is to know your audience. Fans of the sub-genre very broadly fall into two camps—those who are into zombies for the gore and jump scares, and those who aren’t. Please don’t get too upset by that most generic of distinctions. People change. I know I do. Some days I’ll want psychological horror, the next I’ll just want to be grossed out. I think while it’s perfectly natural to change what you read, it’s far more difficult to change what you write. The slapstick horror of a film like Shaun of the Dead is wholly different from the tone of a film like Train to Busan, same as the rural horror of Before Dawn is a million miles removed from the feelgood rush of One Cut of the Dead. The titles I’ve just mentioned are all among my favourite living dead movies, and pretty much all they have in common is zombies. In my experience, it’s nowhere near as easy to switch between light and dark when you’re writing. I tend to specialise in grim dystopian stories about decidedly average people going through hell, and though I’d never rule anything out, I don’t imagine myself writing a feelgood zombie romcom anytime soon. Though never say never, I guess.

Second, set the rules of zombie engagement for your particular story. This might sound silly, but I think it’s important. Romero had his zombie rules, the creators of The Walking Dead had theirs, and I have mine. How do the dead behave? What are their limits? What are their motives? How does the zombie infection spread? Having a clear idea of these things at the outset really helps. You’d be surprised how much the behaviour of your zombies can inform and enhance the development of your story.

But here’s what I think is the key ingredient to writing a serious zombie story in today’s overcrowded market: the story shouldn’t be about the zombies at all, it should be about the people who are left behind to deal with them.

I find it fascinating to think that whoever a zombie might once have been, from the moment of death onwards, they all coalesce into pretty much the same thing. To this end, reanimated corpses are only ever going to be one-note villains. They have limited self-control. You can’t interact with them in any meaningful way, can’t negotiate. It doesn’t generally matter who they were, all you can do is deal with what they’ve now become.

The disease or the radiation or whatever other McGuffin the storyteller has employed to bring about the apocalypse in their tale typically strips the dead of all individuality. Other than their physical height and bulk, most every other characteristic that combined to create the person who’d just died would be shed and all you’d be left with is a shell. More to the point, a shell amongst a vast crowd of shells, often all programmed to act and react in the exact same way. And as time progresses, so the dead would become less physically distinguishable from one another. Colours will fade and leech. Clothing would become encrusted with dirt, grime, blood, and whatever’s left inside the body as it dribbles out through every available orifice. In no time at all, one reanimated corpse would barely be distinguishable from the next.

So, apart from the fact they’re likely trying to kill you, for the most part, zombies are really bloody dull.

For me, the real secret to a memorable zombie story is to focus on everything but the dead. It’s the actions (and interactions) of those who’ve so far survived the apocalypse that make for the most interesting viewing and reading.

For me, the real secret to a memorable zombie story is to focus on everything but the dead. It’s the actions (and interactions) of those who’ve so far survived the apocalypse that make for the most interesting viewing and reading.

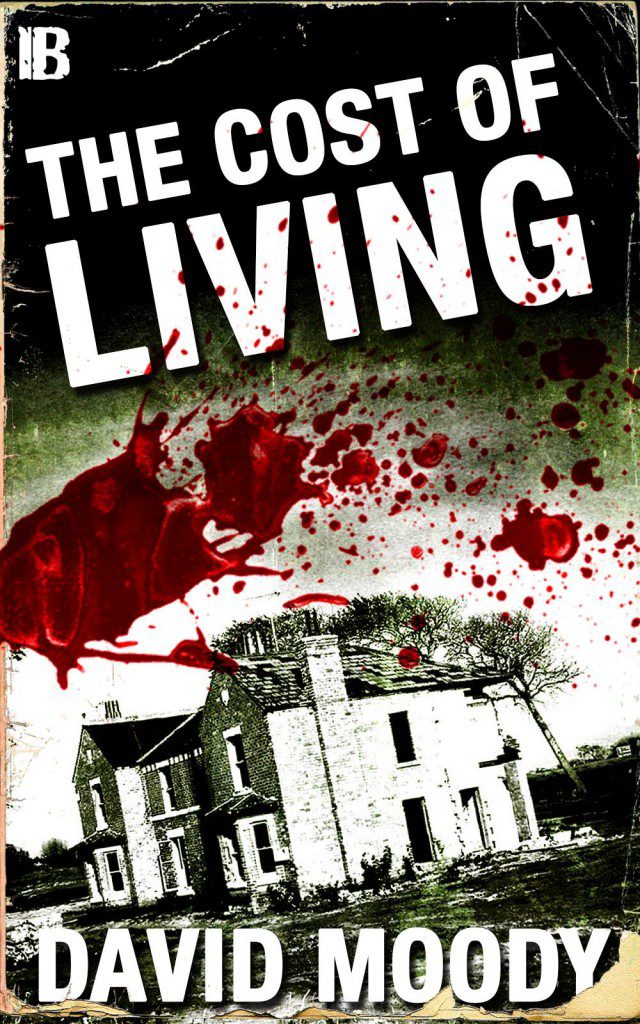

Doing what I do, people often ask me what my own zombie apocalypse survival plan would be. I’ve thought about this far too much. I wrote a novella (The Cost of Living—download it free from all eBook retailers) that was inspired by a genuine argument between my wife and me when we bought a new house and she realised I’d been giving serious consideration to the zombie apocalypse preparedness of every property we’d looked at.

In all seriousness, if the unthinkable happened and I was on my own, I’d try and find out where everyone else was going, then go in the opposite direction. I’d get as much food and water together as I could and find a basement and try to sit out six months or so in solitary confinement. By then, if my research is correct, the dead will be little more than mush and I’d be free to roam again. Guaranteed zombie-free survival.

But that’d make a really shitty book or film, don’t you think?

When you reduce it to basics, I think a good story is simply a journey from one point to another, with a series of things going wrong along the way. In the zombie apocalypse, the bigger the group you’re a part of, the greater your chances are of being hunted out by the dead. I guess what I’m really saying is that it’s more than likely going to be someone else with a pulse who gets you killed.

So, to bring this column to a close, for your best chance of writing a zombie story that’ll stand out from the rotting crowd and be remembered, I think you should:

- Identify your audience

- Define your zombie rules

- Build a cast of strong, relatable characters, shove them together and give them a clear survival goal (or goals)

- Put the lot of them through absolute hell.

I’ve been very critical of the blandness of the dead in this post (Blandness of the Dead—now that has to be the title of the worst zombie movie ever!). But the thing is, they still scare the shit out of me. In my last column, I’ll try to explain why.

DAVID MOODY

Buy David Moody’s books