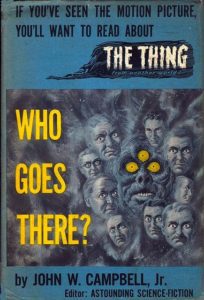

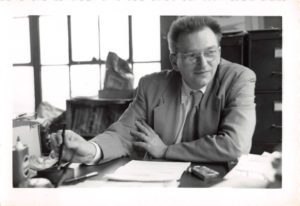

Known for heralding in the ‘Golden Age’ of Science-Fiction, John W. Campbell edited Astounding Stories of Super-Science (later Analog Science Fiction and Fact) from 1937 until his death in 1971. Showcasing writers like Isaac Asimov and Robert A. Heinlein, Campbell introduced the world to the pioneers of science-fiction. With a hard-scientific background, Campbell also wrote several stories of his own before taking the helm at Astounding. One such tale, Who Goes There? is the subject of this month’s explorations of the cold, desolate cosmos.

Known for heralding in the ‘Golden Age’ of Science-Fiction, John W. Campbell edited Astounding Stories of Super-Science (later Analog Science Fiction and Fact) from 1937 until his death in 1971. Showcasing writers like Isaac Asimov and Robert A. Heinlein, Campbell introduced the world to the pioneers of science-fiction. With a hard-scientific background, Campbell also wrote several stories of his own before taking the helm at Astounding. One such tale, Who Goes There? is the subject of this month’s explorations of the cold, desolate cosmos.

How fitting that this novella embraces the bitter chill and isolation of winter. Set in one of the coldest regions in the world, Campbell’s Antarctic tale made such an impact that it has been adapted into film four times, first in the 1950’s, then in the 70’s in an almost recognizable form, later still most famously in John Carpenter’s The Thing, then finally only recently in a prequel/reboot film of the same name. Our focus here is not of the films, but of the inspiration, specifically how this story, though resiliently science-fiction, also captures the mood and tone of weird fiction pitch perfect. There is nothing more harrowing than man attempting to survive the elements. When faced with the frigid cold, isolated from everyday civilization, people tend to become more sensitive to every perceived delusion. Paranoia rules the day, which leads to mistrust and aggression. Combine that with our never-ending quest of discovering who we are, and you’ve got one mighty tale of survival.

The story begins quite in the middle of things as a group of scientists at an outpost in the Antarctic have discovered something buried in the ice. Through the block of ice they can see that whatever it is is clearly not human. After contemplating the ethical question of thawing it and risking harming the men at the base with an unknown bacteria or viral agent, they decide to proceed to examine the thing, believing the theory that only smaller animals with less complex cellular systems can come back to life after a deep freeze.

Of course, they’re wrong.

The scenes here ring out as we’ve come to expect from the Carpenter film. Seeing the film prior to reading the story lends to it a sense of familiarity, as the director pulled character names and bits of dialogue to use in the script. MacReady, Blair, Clark, Dr. Copper, Norris, Captain Garry—they’re all there—in name and in character, though their appearances are more suited to the 1930’s than the late 1970’s. The scene with the huskies in the kennel is a powerful reminder that Carpenter’s source material was a major influence on how he envisioned the film. The story is typical of the science-fiction stories published around that time in 1938, with science providing the backbone of the fantasy. This was several years after the expeditions led by Ernest Shackleton, and during the time of many advances in biological cellular medicine, especially considering human blood. The character dialogue runs the story with very little exposition. These men were scientists, and spoke as such. Regardless, the prose isn’t so laden with jargon that it is unreadable, but is enhanced by the authority of the narrative voice. The story becomes quite believable, which allows for Campbell to spring his trap with skillful design.

The scenes here ring out as we’ve come to expect from the Carpenter film. Seeing the film prior to reading the story lends to it a sense of familiarity, as the director pulled character names and bits of dialogue to use in the script. MacReady, Blair, Clark, Dr. Copper, Norris, Captain Garry—they’re all there—in name and in character, though their appearances are more suited to the 1930’s than the late 1970’s. The scene with the huskies in the kennel is a powerful reminder that Carpenter’s source material was a major influence on how he envisioned the film. The story is typical of the science-fiction stories published around that time in 1938, with science providing the backbone of the fantasy. This was several years after the expeditions led by Ernest Shackleton, and during the time of many advances in biological cellular medicine, especially considering human blood. The character dialogue runs the story with very little exposition. These men were scientists, and spoke as such. Regardless, the prose isn’t so laden with jargon that it is unreadable, but is enhanced by the authority of the narrative voice. The story becomes quite believable, which allows for Campbell to spring his trap with skillful design.

The men slowly become convinced the creature is capable of replicating and imitating other lifeforms. The carcass salvaged from the kennel shows the creature clearly attempting to imitate one of the dogs. If the creature could imitate a dog, then what’s to stop to it from imitating a human? What if the creature already imitated a human? Who among the men is who they say they are?

These questions pose an immediate threat, and consume the rest of the tale. As the men begin to understand what they are dealing with, ultimately turning to MacReady’s blood/heat test to ferret out the Thing, the paranoia comes to an all-time high. These men, isolated from the rest of the world, have come to rely on one another for survival. They’ve become a family, with all the dynamic ups and downs that come with that collective. Trust is paramount to survival, and when that trust disintegrates, survival becomes futile, and nearly impossible.

Early on, the men exhibit a strong dislike of the Thing based on its frozen features, cementing the idea it is evil, and shouldn’t be thawed out.

“You haven’t the slightest right to say that,” snapped Blair. “How do you know the first thing about the meaning of a facial expression inherently inhuman! It may well have no human equivalent whatever. That is just a different development of Nature, another example of Nature’s wonderful adaptability. Growing on another, perhaps harsher world, it has different form and features. But it is just as much a legitimate child of Nature as you are. You are displaying the childish human weakness of hating the different. On its own world it would probably class you as a fish-belly, white monstrosity with an insufficient number of eyes and a fungoid body pale and bloated with gas.”

It’s not long after that that we see their fears are justified:

The three red eyes glared up at him sightlessly, the ruby eyeballs reflecting murky, smoky rays of light.

He realized vaguely that he had been looking at them for a long time, even vaguely understood that they were no longer sightless. But it did not seem of importance, of no more importance than the labored, slow motion of the tentacular things that sprouted from the base of the scrawny, slowly pulsing neck.

The group thins out as the men discover who among them can be trusted. Campbell wastes no time with the horrifying scenes of dealing with the Thing, providing us with short glimpses of the transitions the creature goes through while attempting to escape. If there is one criticism of the story, it’s that those scenes could have been fleshed out a little more, but perhaps that’s more a criticism of growing accustomed to descriptions spoon-fed to us than a writer’s desire to allow our imagination to fill in the blanks. Campbell gives us just enough to let our minds run wild, and what we see is more than enough kindling for our nightmares.

It would be easy to dismiss this tale as a knock-off of Lovecraftian horror, but that’s selling the story short, because there is much more going on here, and at much deeper levels than any homage. Certainly, the influence is there, but Campbell manages to take it further by tying the horror down to the existential question of identity. There is an inherent need to know that our brother is just like us, because anything else is alien, unknown, possibly evil, and a threat. We instinctively seek others like ourselves. The rational mind recognizes people are different in appearance, mannerisms, disposition. But to the paranoid mind, those natural differences become deficits, and when we encounter someone different from ourselves, the need for self-preservation increases, often to aggressive levels of a mob mentality. When faced with an enemy that looks and acts exactly like us, an enemy that has a need for survival so strong it can render its host unaware of the consumption, well that is one of the strongest fears we know of. Campbell manages to capture this fear perfectly with a single question: Who Goes There?

It would be easy to dismiss this tale as a knock-off of Lovecraftian horror, but that’s selling the story short, because there is much more going on here, and at much deeper levels than any homage. Certainly, the influence is there, but Campbell manages to take it further by tying the horror down to the existential question of identity. There is an inherent need to know that our brother is just like us, because anything else is alien, unknown, possibly evil, and a threat. We instinctively seek others like ourselves. The rational mind recognizes people are different in appearance, mannerisms, disposition. But to the paranoid mind, those natural differences become deficits, and when we encounter someone different from ourselves, the need for self-preservation increases, often to aggressive levels of a mob mentality. When faced with an enemy that looks and acts exactly like us, an enemy that has a need for survival so strong it can render its host unaware of the consumption, well that is one of the strongest fears we know of. Campbell manages to capture this fear perfectly with a single question: Who Goes There?

As 2016 comes to a close and we usher in 2017, Exploring the Cold, Desolate Cosmos changes as well. This coming year, in an effort to read as diversely as possible, the profiles here will consist of only writers of the weird and cosmic horror that are men and women of color, women writers, and those writers of the LGBTQ community. First up, we explore the excellent fictions of one the strongest voices in the weird community, Gemma Files. Please join us in January. Until then, Happy New Year!

BOB PASTORELLA