Bringing our tribute to M.R. James to a close, we continue our retrospective on his stories by asking some incredibly talented writers to tell us about their favourite Jamesian tales.

Simon Bestwick – Author of The Faceless and A Hazy Shade of Winter

Simon Bestwick – Author of The Faceless and A Hazy Shade of Winter

Mr Howarth over there has asked me to pick my favourite M.R. James story. Good luck with that; I’m rubbish at picking favourites (except, oddly enough, Ray Bradbury stories, where you’d think I’d be spoilt for choice, but that’s another article.) Still, here goes:

I’ve read and loved many of M.R. James’ stories over the years- ‘Casting The Runes’, ‘Oh, Whistle And I’ll Come To You, My Lad’, ‘A Warning To The Curious’, ‘Count Magnus’- and there’s still quite a few I haven’t got round to reading. Maybe my favourite’s still waiting to be discovered. Till then, though, here’s my current favourite: ‘Wailing Well’.

Unlike most of James’ ghost stories, written for informal gatherings of his friends, this tale was read to the Eton Boy Scouts at their summer camp in Worbarrow Bay, Dorset, on 27th July 1925.

The story nominally contrasts the school careers of two Etonian Scouts- Arthur Wilcox and Stanley Judkins- but poor old Wilcox, other than being wheeled out as A Shining Example To All Boys, doesn’t get much of a look-in. Judkins, as portrayed by James, is a hilariously nasty piece of work- at least, he’d be hilarious as long as you weren’t one of his classmates. But the two boys are both present when their Troop goes camping ‘at W (or X) in the county of D (or Y)’- (in other words, Worbarrow.) There’s a field with a clump of trees in it, called Wailing Well. There are tracks in the grass, but no-one ever goes there. Stanley, of course, will not be told, and- well, that would be telling.

The story’s short, sharp, and to the point; James had to hold a young audience’s attention, and the result is that when the story’s not turning on the chill factor, it’s reminding us how very funny James could be. Which shouldn’t be a surprise; the comic and the horrifying are only a hairsbreadth apart. A comic or ghostly story can fall on its arse in every other way but still succeed on its own terms by wringing the desired response, be it shiver or laughter, from the reader- if the author, like James, has the right kind of skill with words.

‘Wailing Well’ is often funny, often blackly so; when discussing a life-saving competition in which four boys drown, James shows the schoolmasters as more concerned with the gaps in the school choir than the loss of life and perplexed as to why the parents aren’t satisfied with a form letter. Funny, yes, but with a dark edge that taps into the audience’s little irrational dreads. It’s easy to forget, as an adult, just how big and scary grown-ups can appear to a child.

If the humour is disquieting, James pulls no punches on the horror front either, despite (or because) of his audience’s youth. The vampiric, skeletal revenants of ‘Wailing Well’ are among his most terrifying spectres, and the story’s climax shows exactly the kind of relentless dread that James did so well. Even when the comic mode returns at the end of the story, it doesn’t dispel the chill; I wasn’t at all surprised to read that several boys suffered a sleepless night after James’ reading.

‘Wailing Well’ is a cracking little tale, often underrated, and is actually a great introduction to the ghost stories of M.R. James. So if you have children, and you want to terrify them, here’s a good place to start.

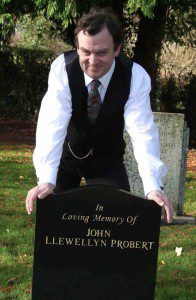

John Llewellyn Probert – This Is Horror film expert and author of The Nine Deaths of Dr. Valentine

John Llewellyn Probert – This Is Horror film expert and author of The Nine Deaths of Dr. Valentine

The 21st of November 1980 was when I was first made acquainted with one of the works of M.R. James. On a gloomy Friday evening I sat in front of the Probert family television set and watched as Michael Bryant (he of Torture Garden and Stone Tape fame) read ‘The Mezzotint’ to me. I would have been thirteen years old and the story, told in a very simple style beside a flickering fire, worked wonders with my imagination. Oddly enough it was shortly after this that I was fortunate enough to see Mr Bryant star in Laurence Gordon Clark’s The Treasure of Abbott Thomas. After that it was a case of a quick trip to the bookshop and M R James quickly became one of my favourite authors, with ‘The Mezzotint’ becoming one of my favourite stories. It has remained so ever since.

There is much in ‘The Mezzotint’ that is characteristic of James’ fiction – the scholar (in these stories such characters often bore a frightening resemblance to my Latin and Greek masters at school) who embarks on an enterprise that initially seems an entirely quiet and genteel pursuit, only for something to be unearthed that is anything but genteel and is quiet only in the most crawlingly horrible way possible. In ‘The Mezzotint’ we have a picture that changes every time it’s looked at, revealing a horrible, emaciated corpse-like creature slowly crawling across the garden of the house that the picture features, and making its inexorable way towards the building. I think the scariest moment when the story was read to me all those years ago was the bit where the creature had disappeared, but one of the downstairs windows was now open. The concept of something that shouldn’t change but does, and of terrible things going on behind the scenes that are either only barely hinted at or not mentioned at all, has done a lot to influence how I write and the kind of stories that I think qualify as ‘good horror’.

Of course there will be those who deny that James’ stories could be described as such, preferring such terms as ‘Pleasing Terror’. I have to say I always found his parade of walking corpses, hideously bony furry creatures, and ‘things of slime’ to be properly horrifying – in the best way. Of course they were often tempered by the author’s own sense of humour, which was always of the ‘Goodness me, now what could one possibly make of the fact that the name on the gravestone had been altered after Mr Blenkinsop met such a ghastly and unfortunate end?’ type that I quickly grew to love, and which tends to find itself into my own stories, no matter how hard I sometimes try to prevent it! My sequel to this story, entitled ‘The Mezzotaint’, is forthcoming in The Ghosts and Scholars Book of Shadows, where you can judge for yourselves if I’ve done justice to this true master of the British Horror Story.

Gary McMahon – Author of Pretty Little Dead Things and The Concrete Grove Trilogy

Gary McMahon – Author of Pretty Little Dead Things and The Concrete Grove Trilogy

Who is this Who is Coming?

Quis Est Iste Qui Venit

As far as I can recall, ‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You My Lad’ was the first M.R. James story I ever read. I came across it in an old book of ghost stories – a battered, spineless hardback edition of an anthology whose title I’ve long forgotten.

I must have been about ten years old when I read the story, and even then it chilled me on a fundamental level. In later years, when I return to James’ masterpiece, I recall the feeling of isolation I felt as I first read about Professor Parkins’ hike along the coast, and the pervading sense of dread when he discovered the whistle…

The plot of the story is simplicity in itself: Professor Parkins is spending a weekend away on the East Anglian Coast. He comes across an ancient cemetery, and digs up an old whistle. Ignoring the Latin inscriptions on the instrument – which are clearly meant as a warning – he blows the whistle. Soon afterwards, he is stalked by what seems to be a ghostly apparition. Or is it merely a spectre created by his own deep-rooted, intensely repressed fears?

This is part of the reason why James always works so well for me. He charts the mental badlands of repressed scholarly types, and the ghosts that are summoned often have a basis in their neuroses. His protagonists are usually physically feeble, introverted, well-read academics who meddle in things they’d be well advised to leave alone. But they never do; they always continue to dig, even when they are given brazen warnings. They exercise free will, and in doing so they open psychological doors through which the restless dead might enter.

James had the knack of using a seemingly mundane phrasing or image to conjure an odd, disjointed, and truly frightening effect – here, among others, it’s “a horrible, an intensely horrible, face of crumbled linen”. He crafted an atmosphere of cumulative dread with his prose, and his ghosts were always memorable. His characters were always flawed, and they rarely deserved the experiences visited upon them, but he never flinched when it came to the scary stuff and always made them sorry they’d poked their noses into whatever murky business they’d unearthed. Yes, those characters might lack depth, and modern readers may find them difficult to relate to, but that’s not the point. Terror is the point, and James nailed it every time.

Jonathan Miller’s 1968 BBC adaptation of the story was a great part of my childhood education in all things ghostly. The icy visuals and stark black-and-white photography, the desolate beach, the psychological subtext, and Michael Horden’s curiously mannered performance all contrived to make it a terrifying experience. The film still works its magic now, whenever I watch the DVD.

It might be Montague Rhodes James’ 150th birthday, but his literary ghosts continue to linger. Wherever there are readers who treasure superbly crafted atmospheric tales, those vengeful spectres will always be welcome. Just whistle, and they’ll come to you, my lad…

DAN HOWARTH