My fascination with decapitation myths (should I admit that?) was sparked by the apocrypha stories of Salome and Judith. Salome’s ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’, a striptease of sorts for her stepfather, King Herod, was performed in exchange for the head of John the Baptist. Judith in comparison was a lot more hands on, stealing into the camp of the invading Assyrian army and seducing their leader Holofernes before beheading him with his own blade. Both these head-huntresses have been much championed in the arts and towards the end of the nineteenth-century they were represented more explicitly as seductive femme fatales, with artists such as Gustav Klimt, Aubrey Beardsley and Gustave Moreau depicting them in highly eroticised poses, often embracing the decapitated heads of their victims.

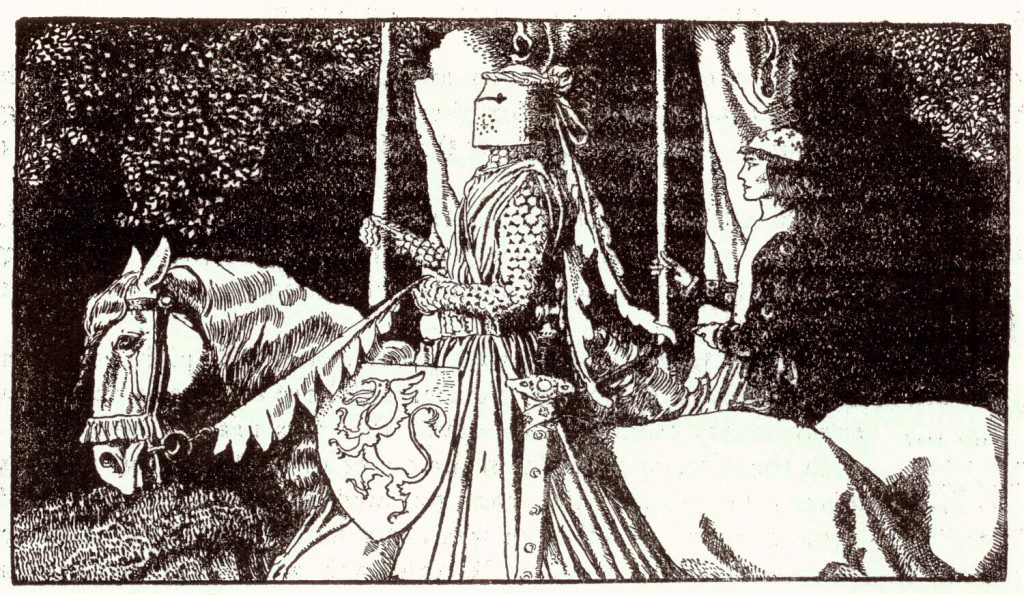

It made me wonder about the link between female seductive power and men losing their heads, so to speak. Which leads me to an old story, the suitably festive 14th Century Middle English poem ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’, a work better known for its adherence to chivalric romance than for what may interest horror readers – its abundance of supernatural imagery. The story begins in King Arthur’s court on New Year’s Day with the festive celebrations in full swing when an unexpected visitor arrives. This “awesome fellow” makes quite an entrance on a mighty horse, brandishing a huge axe. In stature he is described as being so broad and large he “outstretched all earthly men” to the extent that he appeared a “giant on earth”. But what makes him even more remarkable is that he is dressed entirely in the most extraordinary shade of “glittering green”. He makes for such an astonishing spectacle that those gathered believe him to be “a phantom from Fairyland”. But the Green Knight has come with a purpose in mind, putting it to King Arthur that they play a “Christmas game.”

But the Green Knight doesn’t have charades or Monopoly in mind. He asks if there is one among the assembled knights who could strike him with his own axe, provided he can return the same blow a year and a day later. After an unenthusiastic response, Sir Gawain – a green knight himself in terms of experience – takes up the gauntlet, or rather the Green Knight’s axe, and promptly chops off the newcomer’s head. But this isn’t the end of the story. In a scene that may have inspired stories like Irving Washington’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, the Green Knight merely stoops to pick up his severed head, reminds Sir Gawain of their engagement and continues on his merry way.

King Arthur and Gawain put on a show of not being frightened, laughing even as the Green Knight leaves, with the King assuring his wife that, “Such cleverness comes well at Christmastide, like the playing of interludes, laughter and song”. But everyone knows that Gawain, bound by the rules of the game, will die a year later. Before the time of his departure, the court is already grieving for him and King Arthur puts on a great feast, a last supper of sorts, to bid him farewell.

Gawain sets out to locate the Green Chapel, the Green Knight’s home, though he has no idea where it is. He finds instead a castle, arriving on Christmas Day. The lord, Bertilak de Hautdesert, invites Gawain to stay, explaining that the Green Chapel is conveniently only two miles away, and introduces him to his wife, Lady Bertilak. By now Gawain should know better about taking part in games, but when his host proposes a bit of sport, he readily agrees. Bertilak promises to give Gawain whatever he catches when he goes out hunting the next day, if Gawain, who remains at the castle, will give him whatever he gains during Bertilak’s absence. But Bertilak is no sooner out the door when his wife attempts to seduce Gawain. The young Knight tries to fend her off without offending her, yielding a single kiss in the process. When Bertilak returns and hands over the deer he has caught, Gawain kisses him once on the cheek (without saying from whom he obtained the kiss). The same thing happens the next day, with Bertilak giving Gawain a wild boar in exchange for the two kisses Gawain received from his host’s wife. And on the third day, Bertilak gives Gawain the fox he has caught.

This time Gawain keeps something back from his host. Lady Bertilak’s third and final attempt at seducing Gawain is hardest to resist. Sneaking into his bed, dressed voluptuously, and pressing him “hotly” she pushes him to “the very verge”. When Gawain still manages to resist, Lady Bertilak alters her attack. She offers him a ring as a memento of her love, but rings have conjugal associations and Gawain knows this. He declines, and she offers instead her green and gold silk girdle, which she says has magical powers to keep him from harm. Knowing he is about to face a formidable and otherworldly foe, he agrees. But the girdle, a belt of sorts, could also be seen as a sexual symbol, considering that they were designed to hang across the hips, plus any item of clothing removed from the body, represents the act of undressing. Considering that this section of the poem is aligned with Bertilak’s hunting scenes, it forces a comparison between the act of the hunt and its spoils and the rather predatory seductive powers of Lady Bertilak. It’s also interesting that Lady Bertilak’s third attempt involves cunning to entice Gawain, when Bertilak’s offering is an animal known for such a quality. When Gawain accepts the fox from his host but refrains from handing over the girdle, giving him three kisses instead (effectively breaking his bargain) he, too, adopts a sly and cunning attitude in order to keep his spoils and fool his host.

Armed with the girdle, Gawain heads to the Green Chapel to face his adversary. He bows his head to receive the fatal blow but the Green Knight only nips Gawain’s neck. The game is over and the Green Knight reveals himself to be none other than Bertilak. It is all been part of an elaborate trick, a game which both Bertilak and his wife have been forced to play. Behind it all is King Arthur’s half sister, the sorceress Morgan le Fay, who wanted to test the virtue of her brother’s Knights and scare Guinevere in the process. To learn that the supernatural being walking around with his head under his arm at the beginning of the poem is actually just a normal man transformed by the wiles of a sorceress seems to dilute his power, and as an ending it’s perhaps a little disappointing for horror readers. The story is little more than an elaborate prank.

But what is scary is the poem’s concluding attitude towards women. It isn’t just Morgan le Fay, but all women that have the potential to undo men. In a speech, Gawain draws on biblical examples, such as Eve, Delilah and Bathsheba, who tempted men away from a virtuous path. Though they didn’t take their heads like Judith and Salome, they disempowered them nonetheless. Gawain, having survived an encounter with a supernatural green giant, is convinced that women are an even greater foe and he warns “love them but not believe them”. Even the virtuous woman in the poem, Queen Guinevere, later goes to prove herself an adulteress. It is a sad conclusion that Gawain is now distrustful of women, but having nearly lost his head, metaphorically at the hands of Bertilak’s wife, and more literally at the bidding of a sorceress’ Green Knight puppet, it’s perhaps understandable that he is a little jaded.

You can read a translation of the poem in its entirety here.

V.H. LESLIE

If you enjoyed V.H. Leslie’s column, please consider clicking through to our Amazon Affiliate links and buying some of her fiction. If you do you’ll help keep the This Is Horror ship afloat with some very welcome remuneration.