‘You have to think of architecture as an expression of technology’

‘You have to think of architecture as an expression of technology’

David Cronenberg

‘I think we are moving into extremely volatile and dangerous times, as modern electronic technologies give mankind almost unlimited powers to play with its own psychopathology as a game’

J. G. Ballard

Ben Wheatley’s recent adaptation of J. G. Ballard’s High-Rise is meticulously loyal to the original novel, including being set in the mid-1970s. Yet Ballard’s satire on the murderous traits lurking beneath veiled urban civility was supposed to be situated in an ambiguous present; a consumer utopia of ultra-stylish, high-tech mass accommodation. Forty years on, the tenants of Wheatley’s High-Rise might sport the same dated sideburns, smoking habits and flares of the novel but the savagery and horror of their descent into psychopathy resonates just as powerfully—due in no small part to being set in that most conspicuous of settings: the luxury apartment complex. High-Rise might be the latest contemporary horror film (and it is definitely horror, albeit housed alongside elements of erotic thriller, satire and jet-black comedy) to embrace this particularly modern architectural phenomenon, but it is a sub-genre whose foundations run deep.

Roman Polanski’s loosely-connected “Apartment Trilogy” (Repulsion, 1965, Rosemary’s Baby, 1968 and The Tenant, 1976) can be considered amongst the first films to convey the hidden horrors of apartment living in a highly effective, contemporary way. Repulsion draws on the psychological vulnerability of someone living in an apartment at the centre of a hectic urban environment, especially if they are delusional or traumatised to begin with. Carol lives with her mother and lecherous partner, and spends all her free time in the apartment as she feels threatened by normal urban life (even though in reality it is relatively safe). Silence plays a significant role in Repulsion alongside the urban noise beyond the apartment windows, complementing the poised tension of the blackened chiaroscuro imagery, emphasising the ‘cracks’ in the apartment walls as much as the ‘cracks’ in Carol’s mental state. Disrupting the silence are familiar and repetitive domestic sounds, which soon become ominous (dripping taps, creaking doors, gentle footsteps), all adding to the boxy claustrophobia of Carol’s violent, haunted visions. Even the knowledge of real-life neighbours (real-life people) just meters away offers no consolation.  In Rosemary’s Baby, Rosemary and Guy represent modernity: a young, attractive couple working in the entertainment industry, breathing new life into a New York apartment building. The film gradually transforms from the realistic to the sinister, playing not only on the proximity of the neighbours (and the minor overlaps of life which inevitably occurs) but also the transgressive overlap of ideology, of belief and the struggle of the abstract ancient against the compartmentalisation of modern living. Finally, in The Tenant, the morbid (even murderous) dangers of voyeurism into the lives of those around us is examined, and how mass accommodation all but encourages us to pry into the lives of those we may never even know, due simply to our geographical closeness. Polanski exploits the compactness of apartment living to get to the horror of the internal-external: the external world creeping, uninvited, into our homes, or the claustrophobia of neuroses spilling over into the home. Compared to the ominous scale of the average gothic horror film setting, doesn’t an apartment seem like a much more logical, intimate place to haunt?

In Rosemary’s Baby, Rosemary and Guy represent modernity: a young, attractive couple working in the entertainment industry, breathing new life into a New York apartment building. The film gradually transforms from the realistic to the sinister, playing not only on the proximity of the neighbours (and the minor overlaps of life which inevitably occurs) but also the transgressive overlap of ideology, of belief and the struggle of the abstract ancient against the compartmentalisation of modern living. Finally, in The Tenant, the morbid (even murderous) dangers of voyeurism into the lives of those around us is examined, and how mass accommodation all but encourages us to pry into the lives of those we may never even know, due simply to our geographical closeness. Polanski exploits the compactness of apartment living to get to the horror of the internal-external: the external world creeping, uninvited, into our homes, or the claustrophobia of neuroses spilling over into the home. Compared to the ominous scale of the average gothic horror film setting, doesn’t an apartment seem like a much more logical, intimate place to haunt?

In a more explicit capacity, the apartment block setting has been exploited in more visceral ways in recent years. Paco Plaza’s [REC] (Spain, 2007) and Yannick Dahan and Benjamin Rocher La Horde (France, 2009) are both “zombie” films set in contemporary urban European cities. [REC] begins as a run-of-the-mill documentary-style news show, before turning into a full zombie horror once it enters a Barcelonian apartment building. Although the building itself is old, the residents represent the modern urban demographic – younger and senior citizens, families and singletons – living alongside each other (in varying degrees of mutual tolerance). The “virus” spread by the living dead completely collapses the urban narrative, raising questions about tolerance, overpopulation and survival in modern Europe. La Horde, conversely, plays on the notion of crime and hierarchy in deprived inner-city high-rise housing. The buildings that the police, drug deals and innocent civilians have to hole-up in together to escape the living dead take on the appearance of multi-storey mausoleums rather than places of safety and harmony.

In a more explicit capacity, the apartment block setting has been exploited in more visceral ways in recent years. Paco Plaza’s [REC] (Spain, 2007) and Yannick Dahan and Benjamin Rocher La Horde (France, 2009) are both “zombie” films set in contemporary urban European cities. [REC] begins as a run-of-the-mill documentary-style news show, before turning into a full zombie horror once it enters a Barcelonian apartment building. Although the building itself is old, the residents represent the modern urban demographic – younger and senior citizens, families and singletons – living alongside each other (in varying degrees of mutual tolerance). The “virus” spread by the living dead completely collapses the urban narrative, raising questions about tolerance, overpopulation and survival in modern Europe. La Horde, conversely, plays on the notion of crime and hierarchy in deprived inner-city high-rise housing. The buildings that the police, drug deals and innocent civilians have to hole-up in together to escape the living dead take on the appearance of multi-storey mausoleums rather than places of safety and harmony.

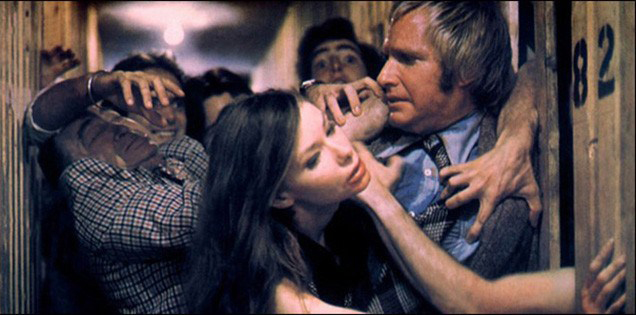

If the contemporaneous horror of Wheatley’s High-Rise has a direct predecessor, it has to be Shivers (David Cronenberg, 1975). Like much of Cronenberg’s early work, Shivers provides nauseating yet addictive viewing in equal measure not least because the body-horror element is usually strange and counter-intuitive viewing; enough to make sure you keep watching just to figure out exactly what you are watching. But also, being set in a Brutalist, function-over-design apartment complex, the horror of Shivers becomes compounded by the domesticity of it: the familiarity of setting makes it feel as if it could all happening to you, in your neighbourhood, maybe in your home and in the very room you are sitting in.

High-Rise, like Shivers, attempts to seduce part of us with consumer features (the promotional slide show exemplifying the building’s facilities, and other promotional materials). This allows us to independently buy into the horrors to come, as if it’s our own fault we were seduced by it all in the first place. In Shivers the new residencies, department stores, dentist surgeries and hallways are presented conspicuously empty at first – still images, lifeless and immediately haunting in an odd way – before cutting to a sexually-motivated murder scene. High-Rise, conversely, begins in media res with the majority of the violence having already been committed, and instead we find (surviving) protagonist Dr Robert Laing eating a barbecued dog’s leg whilst contemplating the hideous events of the recent past.

Shivers‘ lurid cinematography turns the viewer into a witness—a voyeur even—within the blandly-decorated, boxy apartment to observe the horrors first-hand. Conversely, High-Rise, with its objective, removed narration (reflecting Ballard’s signature prose-style perfectly) gives the reader an almost anatomical tract, stripped of sensation.

It is significant that, in 1975, Cronenberg and Ballard should be addressing similar themes at exactly the same time; Ballard from a psychological realm, Cronenberg from the physical—Shivers exposes the external threat (the body’s susceptibility to parasitic invasion); High-Rise analyses the internal threat (the mental nucleus, a regression into deliberately-buried atavistic impulses). Cronenberg cites the impact of Toronto’s commercial and domestic redevelopment as his chief inspiration. In a 2014 interview with Filmmaker Magazine, he comments on how the cold, functional urban developments he witnessed springing up during the late 1960s and ’70s compounded “the loneliness, the smallness of human beings,” and helped him identify “the relationship of technology with human beings.” Ballard instead saw equally sterile developments in England as evidence that “people are locking their doors and switching off their nervous systems”. He believed that such enclosed living was a mistake as “a certain level of crime is part of the necessary roughage of life. Total security is a disease of deprivation.”

It is significant that, in 1975, Cronenberg and Ballard should be addressing similar themes at exactly the same time; Ballard from a psychological realm, Cronenberg from the physical—Shivers exposes the external threat (the body’s susceptibility to parasitic invasion); High-Rise analyses the internal threat (the mental nucleus, a regression into deliberately-buried atavistic impulses). Cronenberg cites the impact of Toronto’s commercial and domestic redevelopment as his chief inspiration. In a 2014 interview with Filmmaker Magazine, he comments on how the cold, functional urban developments he witnessed springing up during the late 1960s and ’70s compounded “the loneliness, the smallness of human beings,” and helped him identify “the relationship of technology with human beings.” Ballard instead saw equally sterile developments in England as evidence that “people are locking their doors and switching off their nervous systems”. He believed that such enclosed living was a mistake as “a certain level of crime is part of the necessary roughage of life. Total security is a disease of deprivation.”

In Shivers the deterioration of civility throughout the building is caused directly by a slug-like parasite fed into the building’s water and disposal systems by the recently-deceased Dr Emil Hobbes (also a resident). Hobbes saw the creature as “a parasite that can do something useful,” as it allows people to regain supposedly repressed natural—yet violent—sexual urges. The creature may transform its host once it enters them, but it does in some way allow them to simply live also; to act impulsively against the sterile inevitability of their engineered domestic environment. In this way, the manipulative science of Hobbes is perhaps no more manipulative than the apartment complex itself. If a mad scientist envisages water pipes and waste chutes as the perfect transportation network for his “life forms”, what sort of “life forms?” were the apartment’s designers picturing as inhabitants in the first place?

If seen in terms of social or cultural engineering, the residents in High-Rise and Shivers make us ask one question: where did they come from before they moved in? Through their inhuman rituals they are a subaltern populace – out of place, out of time, and effectively running the risk of haunting their own homes. Where the residents in Shivers include a select group of medical professionals (scientists, physicians and nurses involved in various sexual affairs) the residents in High-Rise include important media types (television producers, documentary-makers, actors). Richard Wilder, a volatile, alcoholic filmmaker completely relishes the savagery and degradation he partakes in, and even begins obsessively filming the looting, rape, murder and cannibalism not only to document it but because he intrinsically senses it is his job to do so: to perpetuate the “media landscape” (as Ballard coined it) and to help continually suppress the viewing populace with imagery and sensation. Wilder, like most other characters, is lost not only to their basest impulses but also to the entrapment of ego: the addiction of self-importance. But at the very least, at the end of High-Rise, Dr Robert Laing has managed to retain that one humanising trait even after the horrors he has been involved in: reflection, a sense of context as to how and why the descent into savagery has occurred. In Shivers, no such post-apocalyptic resolution is reached and instead all traces of civility and reason are consumed (like Roger St. Luc being drowned in the perfectly maintained municipal swimming pool).

Whether set in Cronenberg and Ballard’s mid-70’s, or early 2016, the modern luxury high-rise seems to exist outside of time; an architectural phenomenon neither embracing nor rejecting the era it is built in, but existing detached from everyday society as its own thing entirely. Due to its architectural and cultural displacement, the modern luxury high-rise sits uncanny within the landscape; reminiscent of the domestic environment yet somehow nothing like it due to its sheer expense and elitist connotations. It is unheimlich, or unhomely, to quote Freud, making it the ideal location for the kind of unsettlingly-close horror which perhaps exists just one reality—perhaps just one wall—away from us.

Whether set in Cronenberg and Ballard’s mid-70’s, or early 2016, the modern luxury high-rise seems to exist outside of time; an architectural phenomenon neither embracing nor rejecting the era it is built in, but existing detached from everyday society as its own thing entirely. Due to its architectural and cultural displacement, the modern luxury high-rise sits uncanny within the landscape; reminiscent of the domestic environment yet somehow nothing like it due to its sheer expense and elitist connotations. It is unheimlich, or unhomely, to quote Freud, making it the ideal location for the kind of unsettlingly-close horror which perhaps exists just one reality—perhaps just one wall—away from us.

R. P. FOX