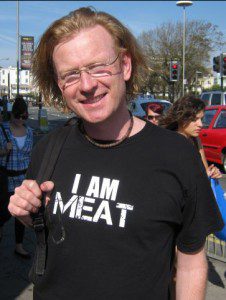

Joseph D’Lacey is one of the most exciting writers in horror today. He has been affectionately dubbed an eco-horror author for his morally complex and ecologically minded fiction. His achievements include the Best Newcomer award in the 2009 British Fantasy Society Awards for MEAT, a book that prompted Stephen King to declare, “D’Lacey rocks!” We caught up with him to discuss the genre, ecology, spirituality, the London riots and much more.

Joseph D’Lacey is one of the most exciting writers in horror today. He has been affectionately dubbed an eco-horror author for his morally complex and ecologically minded fiction. His achievements include the Best Newcomer award in the 2009 British Fantasy Society Awards for MEAT, a book that prompted Stephen King to declare, “D’Lacey rocks!” We caught up with him to discuss the genre, ecology, spirituality, the London riots and much more.

When did you start writing and what was the initial attraction to horror?

JDL: I started writing poetry when I was eight years old, and wrote a couple of stories at school that were largely ignored. I first read horror when I was ten. The sex, violence and concepts outside of everyday experience just floored me. On a perceptual level it suggested there was something more going on in the world around me than I was able to see and that’s always been my fascination.

Works that have had a big effect on me both within and without the genre include Night Shift by Stephen King, The Great and Secret Show by Clive Barker, The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, the Unbeliever by Stephen R. Donaldson, Patrick Tilley’s ‘The Amtrak Wars’ and The Forge of God by Greg Bear. SF and Fantasy have been equally enjoyable for me as horror – sometimes more so. I’ve always loved King’s early works, particularly his novellas, but it was James Herbert who first opened my eyes to the darkness. When I started writing, I suppose I worked at the confluence of all three genres. I probably still do now. I don’t see myself exclusively as a horror writer.

I didn’t begin writing seriously until I came up with some illustrated verse for kids– about thirteen years ago now. It was turned down by all the UK children’s publishers. I started my first two unfinished novels about the same time. The first novel I completed was a black comedy that also never saw the light of day. But I was committed by then and have been ever since.

I know I’ve said both James Herbert and Stephen King turned my head in the early days, but it was a novel called Leviathan by John Gordon Davis that first blew my mind. I was far too young when I read it – eight or nine, perhaps. It was a swashbuckling, maritime adventure in which an ecologically minded oceanographer, sickened and angered by whaling, puts a crew together to capture and hold to ransom a vast Russian whaling boat. They train up, board the ship and it goes horribly wrong. Our heroes are hacked up with blubber knives, lots of Russian seamen get machine-gunned and there was loads of bad sex. At least that’s how I remember it. That book opened up a universe of pure possibility.

So horror is a very broad term for me, taking in a range of human experiences, whether possible or imagined. I’ve always been interested in the weird or anything at or beyond the periphery. I love the sacred, the profane and the arcane equally. When I was a kid I went through a phase of doing tarot readings for my friends. It utterly entranced me at the time – I had the Rider Waite deck and several books on how to use the cards. But I stopped doing it when I realised I was getting it right.

Speaking of tarot readings and spirituality, what are your own beliefs and how do they influence your writing?

Speaking of tarot readings and spirituality, what are your own beliefs and how do they influence your writing?

JDL: From a very young age, I knew I wasn’t going to be a religious person, but in the moment I understood that, I also realised I was a deeply spiritual person – at the very least deeply concerned. I’ve never stopped wondering about the magic of existence, consciousness and perception – even though I have very little ‘knowledge’ to show for it. In the last ten or fifteen years, I’ve developed a strong connection to the land, the environment and living things around me. A walk in the woods is an interaction now, where once I was merely a spectator.

I have a very good friend who says that this is it: one life, one shot. I don’t believe that. There are so many things I can’t explain which hint at something else, something more, going on beyond what we can sense. Perhaps this comforts my ego; the poor thing can’t deal with its inevitable destruction.

From a writer’s perspective, I think I learn about myself by writing on various subjects and I would say there’s an element of spirituality in my work – or perhaps just an element of my own endless dissatisfaction and questioning.

“Despite the best intentions of the majority of devout people, religion brings people together by excluding others.”

I don’t go to church other than to celebrate a union, a new life or a life passing. Religion, with its edicts and dogma, is not for me. It’s probably no fault of religion itself but the people involved in its organisation tend to be tainted by the wealth and standing that their involvement gives them. It’s far too much like a corporation to be of any interest to someone like me. Despite the best intentions of the majority of devout people, religion brings people together by excluding others. Raise a banner or icon over a group of people, give the group a name and you’ve created the first conditions necessary for war. I’d rather get together with others of a like mind for a party and commune with the world of spirit on my own.

How do you feel about the ‘eco-horror’ label?

During the marketing and publicity process for MEAT, we decided that ecologically-minded fiction wasn’t unique. Margaret Atwood’s ‘Mad Adams’ trilogy is a popular example. Whether the term eco-horror already existed or not, I don’t know, but I quite liked the sound of it. It was ‘Zeitgeisty’.

Garbage Man, which paralleled the burial of secrets with the burial of rubbish, happened to fit the same label, even though that wasn’t entirely intentional on my part.

Since then I’ve gone on to write more fiction which falls into broadly the same conceptual catchment area but whether I’ll stay in that groove going forward I don’t know. Either way, I’ve enjoyed being considered an eco-horror writer.

MEAT, Garbage Man and The Kill Crew are apocalyptic works, what attracts you to the subject matter and will this continue?

MEAT, Garbage Man and The Kill Crew are apocalyptic works, what attracts you to the subject matter and will this continue?

JDL: It’ll continue alright! It’s already a theme in much of the work I’ve written since then; fiction that hasn’t yet seen the light of day.

When there’s a meltdown of social, political and economic structures, anything goes. People become animals again. It’s great for fiction because it’s a matter of life and death on every page.

“I love the idea that someone could walk down a once thronged and chaotic street where now there is no noise”

I’m attracted to eschatological themes and always have been. The idea that our world could end is fascinating in the most terrible way. Is humanity a failed mechanism, fundamentally and irreparably flawed? Perhaps, like other species that have come and gone, we simply represent a phase of development in the great experiment of existence. When faced with the end, how do we react? What remains important when you strip everything, even the possibility of survival, away? There’s endless material there. I love the end of the world.

And I love the idea that someone could walk down a once thronged and chaotic street where now there is no noise, no movement and the possibility that there is no-one else left alive. At least, nothing human.

I’m sure I’ll be spending a lot more time perched on the brink of Armageddon.

Did last year’s riots provide a glimpse at what it would be like if we had a breakdown and how do you relate the riots to fiction?

JDL: There have always been riots. If you sit down and read a bit of history you’ll see plenty of mob action. It’s a symptom of unhappiness, disillusionment and hopelessness. It’s not even as complicated as that, probably – plenty of individuals are bored and pissed off with their meaningless, joyless existences. I can imagine a riot would have provided a good deal of excitement for people with nothing else to look forward to: a sense of something, anything, happening. We all need a purpose and good, simple reasons to be part of a society that works. If we don’t have that purpose and those reasons and if we’re lied to and let down by our leaders, riots are inevitable.

From a work point of view, it’s interesting it happened when it did, though. I’d been writing a novella called These Dreams of the Dead. In it a character diarises his descent into madness. Before the riots I couldn’t see the ending, whereas afterwards I could.

You said there wasn’t an ending to your story up until that point, how much do you plan before writing?

You said there wasn’t an ending to your story up until that point, how much do you plan before writing?

JDL: I don’t plan. I don’t know the names of the characters or what will happen in the story. Over the course of ten novels and numerous novellas and short stories I’ve had little or nothing written down to start with. In the case of The Kill Crew, it was nothing more than a three-word phrase that struck me. I didn’t know what The Kill Crew was, where they were or what they did, but I wanted to find out. Once I started writing, I could hear the protagonist talking to me the whole time. I couldn’t have planned that story. I’m wary of planning because, speaking for myself here, it can really dampen an idea. It’s like letting the power dissipate before you’ve manifested something.

However, over the last year or so, I’ve been collaborating with screenwriter Jeremy Drysdale on a series of books for teenagers. He plans everything. The partnership has worked really well and I’ve learned a lot about the value of preparation – never thought I’d say that! Once our first novel was in full swing, beyond the planning stage, I was writing a chapter a day without ever worrying about what might happen next. As a result I’ve since laid out a plan for one of my next novels and may even come up with a chapter outline before I start!

What was initial idea for MEAT and when did you start the research?

JDL: It came from years of pondering a double standard. I generalise, of course, but I’d say most of us don’t want a hand in killing an animal – for any reason – yet most of us are perfectly happy to eat one after the fact. I’m also interested in the idea of karma, the chain-reaction of cause and effect that echoes through time; if there is such a thing and to harm living things is, essentially, wrong, then what are the repercussions?

At the time, I’d already written books about terminal illness, vampiric creatures roaming wild forests, human spiders and mind control. I’d been wanting to write balls-out, no-holds-barred horror for a while; to really get down to the knuckle. I knew the theme of mass slaughter for food would give me that opportunity. I just needed a story for it, a conflict, a world.

I almost never take characters from real life, but there was a man I used to see along the roadside, running every day between my village and the nearby town. He carried a terribly heavy pack on his back and he must have been running at least six or seven miles. Despite the burden he always had a big grin and I couldn’t help but wonder why. Was he punishing himself for something? He became the genesis of Richard Shanti and his inner conflict became the thread that held MEAT together and drove the story forward.

“The brutality and ignorance with which animals are treated has to be seen to be believed.”

I carried out a great deal of research for MEAT. I wouldn’t usually – It can quickly become another excuse for not writing and I don’t need any more of those – but I knew that whatever happened in the novel had to happen exactly as it would in a slaughterhouse, in real life. It had to be as authentic as possible. I read about how best to slaughter large numbers of animals as efficiently as possible – the meat dollar turns on speed – and how to keep animals calm enough, long enough to dispatch them without fuss.

I watched hours of the most brutal and uncompromising footage, a lot of it filmed undercover. I saw not just pigs, sheep, chickens and cows factory-farmed, mass transported and abused but also cats, dogs and horses. The brutality and ignorance with which animals are treated has to be seen to be believed. Much of it occurs long before the animals go to slaughter. Long before they meet the bolt-gunner who stuns them prior to their throats being slit for exsanguination. And the numbers of animals killed to satisfy a demand for meat at almost every meal is so staggering it’s almost incomprehensible. I wanted that cold disregard to come through in the novel, so the research seemed worthwhile in this case.

MICHAEL WILSON

—

If you enjoyed our interview with Joseph D’Lacey and want to read more of his fiction, please consider clicking through to our Amazon Affiliate links and purchasing a new book today. If you do you’ll help keep the This Is Horror ship afloat with some very welcome remuneration.