When you think of British supernatural television, Stephen Volk will always spring to mind. He is, without a doubt, one of the Godfathers of British horror screenwriting. Amongst his classics is Ken Russell’s Gothic, although he is perhaps best known for the creation of two cult television programmes, Afterlife and the sublime Ghostwatch.

When you think of British supernatural television, Stephen Volk will always spring to mind. He is, without a doubt, one of the Godfathers of British horror screenwriting. Amongst his classics is Ken Russell’s Gothic, although he is perhaps best known for the creation of two cult television programmes, Afterlife and the sublime Ghostwatch.

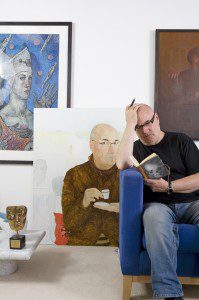

Jim Mcleod was fortunate enough to sit down with Stephen recently.

Hello Stephen, it’s an honour and a pleasure to get the chance to talk to you again. How are things with you?

SV: Not bad, though times are tough, as everybody knows. The cuts mean that everybody is totally risk-averse at the moment, so getting any decision made is murder. After several months of writing treatments, though, I have a script commission, possibly two. And a rewrite on an older project of mine in which there’s some new interest. So I’m suddenly busy. Also hoping that some cash will come in, which would be nice.

So who exactly is Stephen Volk?

SV: If I knew that I wouldn’t need to be a writer!

How did you get into screenwriting?

SV: I drew pictures and wrote as a kid growing up in South Wales. I went to art school. I went to film school, but I also wrote stories the whole time. I felt I was a split personality between the visual and the verbal until a tutor at film school called Bill Stair (who was both a writer and art director, and worked a lot with director John Boorman) told me, no – you’re a writer, but a screenwriter. It was the first time anybody had pointed that out to me! I loved cinema and I wanted to write stories as if I was watching them, so that’s what I did, and I did it right through my first job which was in advertising, writing at night time, sending scripts off, getting them back, sending them off again. For ten years I did that, until somebody optioned my screenplay Gothic for about one and a half peanuts, then I got an agent and my agent sold it to Virgin Films. But I had several other screenplays written by then. Nowadays there might be a more formal route of going to film school to be a screenwriter on a Screenwriting course, but it was more haphazard for me back in the 1970s. So Gothic was my first screen credit in 1986 with Ken Russell (RIP) directing.

How does screenwriting differ to writing prose?

SV: A good prose writer can learn screenwriting, and vice versa. Writing is writing. It’s about using your imagination and knowledge of human beings, and the ability to convey ideas and edit them when you’ve got them. Writing a screenplay, though, you have to be immensely concise, to the bone really, and always be the camera and the microphone: if you can’t see it or hear it don’t write it down in the scene.

The real skill is in cutting

You have to be conscious of the ticking clock, how long a scene runs, and it has to be 100 pages or 100 minutes or you are dead. And it’s not description, it’s incident. Things have to happen. So the real skill is in cutting, cutting, cutting because less is more and the narrative of film is merciless – you can’t divert into tributaries as you can in a novel. Point of view and a strong line of action is vitally important. But with all writing the main thing is theme and metaphor. As Paul Schrader said, his theme in Taxi Driver was loneliness and his metaphor for the theme was the taxi driver. (But you needn’t know that when you start writing. You might not discover your theme until draft eight.) On the other hand, what I love about short story writing (apart from the fact it can be done in days rather than years!) is that you can get in the head space and just let it flow with the voice in your head and the language. And nobody tells you what to do!

You predominantly write in the supernatural genre. What is the appeal of genre for you?

SV: John Ford’s chosen milieu was Westerns. Even when they weren’t set in the Wild West, they were set in Galway or something, they were still Westerns in mentality. Similarly, I think there’s something about the supernatural tales I grew up reading and watching that just chimed with me and I wanted to be in that world. Primarily they were thrilling. I loved the idea of something unlikely or impossible added to a story, not just it being about mundane reality, and the fact that that unnatural element you introduce isn’t just window dressing but it illuminates theme and character: it enables the story to be something it otherwise wouldn’t be. I think generally I like “cinema of the imagination” rather than social realism (which I find formulaic and unrewarding), but specifically supernatural or ghost stories can be great metaphors for grief, hurt, the past… It’s a wonderful playground and the territory just always attracts me. Plus, I believe we are all a mixture of the rational and irrational urges, these two things battling, wanting to believe but terrified if these things are true, so I think it’s our essential nature you can sometimes dramatise.

People are perhaps most familiar with you from Ghostwatch. Do you ever feel like saying there is more to me than Ghostwatch? I’ve always wondered if writers ever feel the same way as bands getting asked to play the same song over and over.

People are perhaps most familiar with you from Ghostwatch. Do you ever feel like saying there is more to me than Ghostwatch? I’ve always wondered if writers ever feel the same way as bands getting asked to play the same song over and over.

SV: I suppose I do, but I don’t mind that people remember it twenty years later! At the time, 1992, it was like it happened overnight (literally) and there was this angry flurry of protest in the media and it was gone. I thought really it was the kind of event if I had been back in school I would have loved, and it seems that was the way it hit a lot of people, or so I’ve heard since. I’ve done other things. I’ve written about six feature films now. You don’t know if they’re going to work or find an audience. In fact you’re often disappointed in them yourself, but the main thing you hope for is a pay day that enables you to keep on writing. And if you can keep writing you might get lucky: that’s it.

“If people only know me from Ghostwatch they will wonder what the hell I’ve been doing since 1992 but the reality is I haven’t stopped!”

So I keep writing and on and off things happen, like Shockers or Octane or Superstition. But I wrote and created the ITV series Afterlife which ran for two seasons starring Lesley Sharp and Andrew Lincoln. That was fairly well liked, I think, and I’m pleased about that, and The Awakening is just out with a reasonably high profile push behind it from StudioCanal. If people only know me from Ghostwatch they will wonder what the hell I’ve been doing since 1992 but the reality is I haven’t stopped!

2012 marks the twentieth anniversary of Ghostwatch, are there any plans to mark this occasion?

SV: Not that I know of. I’d like a special edition DVD to come out, one containing maybe an extra disk of proper interviews with the participants and a proper documentary about what happened, but that is pie in the sky at this stage unfortunately, though the material all exists. I have a feeling if anything at all happens beyond a raft of individual screenings up and down the country it will be a last minute “kick-bollock-and-scramble” thing by the BBC or something, typically. Or nothing. We’ll see. I don’t have any control over it.

Looking back at the intervening years, how well do you think it stands up?

SV: I look at it a lot with audiences and it stands up OK. Listen, after 20 years I’m not going to pick holes in it: it is what it is. It’s a bit dated, but if people have any sense at all, they’ll forgive it for that. You get a lot of giggles when you show it nowadays of course. People think they’re smart. But it always gets a great round of applause at the end. I sense that people enjoy it. The audience is often a 50-50 split of those who’ve seen if before and those who haven’t and it’s always a bit of an occasion. It’s great. You have to remind them of the context of the time though, way back when we made it. That this was at the very beginning of ‘reality TV’ – way before Blair Witch or Most Haunted.

And how much influence do you think it has had?

And how much influence do you think it has had?

SV: Well, exactly that! The whole ‘camcorder horror’ style of drama, which you can trace right to Paranormal Activity – and we know the director of that had been influenced by Ghostwatch because he said so. We invented the night vision stuff that Most Haunted and a hundred other shows have just run into the ground. But Ghostwatch wasn’t Most Haunted, which is a crass, idiotic pseudo-spiritualistic entertainment show – Ghostwatch was a drama designed to provoke you and get you to think about your complicity in the TV shows you watch, get you to think about how you take information on your screens for granted, think about how you don’t question experts, about how you need to question even what you see with your own eyes…

Have you ever been tempted to return to the format and do a sequel?

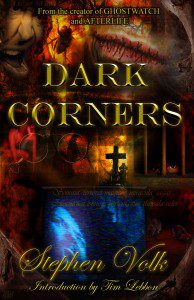

SV: No. People ask, but it’s a one-off. Though somebody asked me for a story on the tenth anniversary and I wrote a sequel in short story form, called ‘31/10’, which was nominated for a Horror Writers Association Bram Stoker Award. It’s on my website, and in my short story collection Dark Corners (Gray Friar Press) if anybody wants to read it.

If you enjoyed our interview and want to read Stephen’s fiction, please consider clicking through to our Amazon Affiliate links. If you do you’ll help keep the This Is Horror ship afloat with some very welcome remuneration.