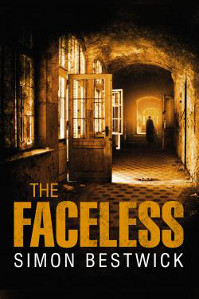

Publisher: Solaris Books

Publisher: Solaris Books

Paperback (412 pgs)

The Faceless by Simon Bestwick is a densely plotted horror novel that is genuinely scary. The fear taps into the reader in a sinister, nerve-fraying manner in which the tension is ratcheted up until it’s almost unbearable to carry on reading yet unthinkable that you should actually stop. The reading light will stay on long after you finish reading.

There are three main viewpoints utilised by the author. The first, and least satisfying, is that of the team of detectives involved in trying to find a missing girl. In charge is Detective Chief Inspector Joan Renwick, still affected by a previous missing-person case which ended badly. He is assisted by DS Mike Stakowski. Their relationship is well-developed with a believable level of banter and respect, along with hints of an unrequited attraction, particularly from Mike’s view, which makes for a great pair of characters. Unfortunately, the rest of the police department is a little underdeveloped and the number of different officers mentioned makes it a hard to follow who’s who. There’s a sense that the numbers involved are an obstruction to the author, too, so when a large portion of the squad is dispatched in a selection of grizzly ways it’s something of a relief.

The second narrative viewpoint is that of TV psychic Allen Cowell and his driven sister Vera. Here the revelations in their back-story provide some of the most effective and gut-wrenching scenes of the novel and showcase Bestwick’s powerful yet restrained prose, where just enough detail is given to allow reading between the lines to ensure the scenes are not gratuitous. This shows a level of trust both in the reader and in the writer’s own ability, which sets these scenes apart from the average horror novel. Allen’s spirit guides are the three boys who were left behind when he and his sister made their escape from Kempforth, and the scenes when they appear to Allen are amongst the most chilling in recent horror fiction. There is also an aspect to the sibling’s relationship that makes the skin crawl for less supernatural reasons.

The final protagonist is Anna Mason, a single woman struggling to juggle the demands of family, a bereaved brother, his young daughter and their elderly gran. She harbours a desire to escape to the big city to explore her sexuality and aspirations. Having an interest in local history means much of the exposition falls to her, although this is well handled and never feels forced. Anna is the most likeable character in the book, which helps to make the scenes where she is at the centre of the peril all the more nerve-wracking. Ultimately she is the character who pushes the narrative along the most.

Interspersed with the chapters from these viewpoint characters are first-person testimonies from some of the soldiers who were affected by the events of World War One, and particularly Passchendaele, who, on their return, find themselves treated at Ash Fell. These passages add a sense of the violence and suffering endured by the soldiers of Kempforth but ultimately they slow the narrative down, bringing the reader out of the main story when it’s at its most engrossing. The voices are indistinct and the temptation to skim-read these passages in order to get back to the story is there. There is also a coda at the end of the book that is similar to the recently released A Cold Season by Alison Littlewood, which veers close to cliché and, as in the case of the aforementioned novel, weakens what is otherwise a strong climax to a superbly realised novel.

The evil beings of the title are the ‘Spindly Men’, figures of local legend in the town of Kempforth, who are said to have risen from Hell and who, as they have no faces of their own, seek out people willing to make masks for them to wear in return for the power to command their actions. This legend is used by the group responsible for the abuse of Allen and Vera as children in order to disguise their real identities. This blurring of the lines gives a great ambiguity to the opening third of the novel, where the reader is not quite sure if the supernatural element is real or imagined.

The Faceless contains a level of craft and execution that, alongside the work of Ramsey Campbell, Conrad Williams and Gary McMahon, goes a long way in restoring the reputation of the horror novel, given the genre’s inconsistency following on from the 80s boom. Commissioning editors at imprints such as Angry Robot, Solaris and Jo Fletcher Books should be praised for having faith in new writers tackling tough subject matter with intelligence and imaginative flair. Bestwick has these qualities in abundance and is certainly a name to watch out for in the future.

ROSS WARREN

If you enjoyed our review and want to read The Faceless by Simon Bestwick please consider clicking through to our Amazon Affiliate links. If you do you’ll help keep the This Is Horror ship afloat with some very welcome remuneration.

Buy The Faceless by Simon Bestwick (UK)

Buy The Faceless by Simon Bestwick (US)

1 comment

Another great review Ross, but I disagree with you about the testaments – I thought these were really cleverly done and were placed very carefully in the text to add to, rather than distract from, the main narrative.