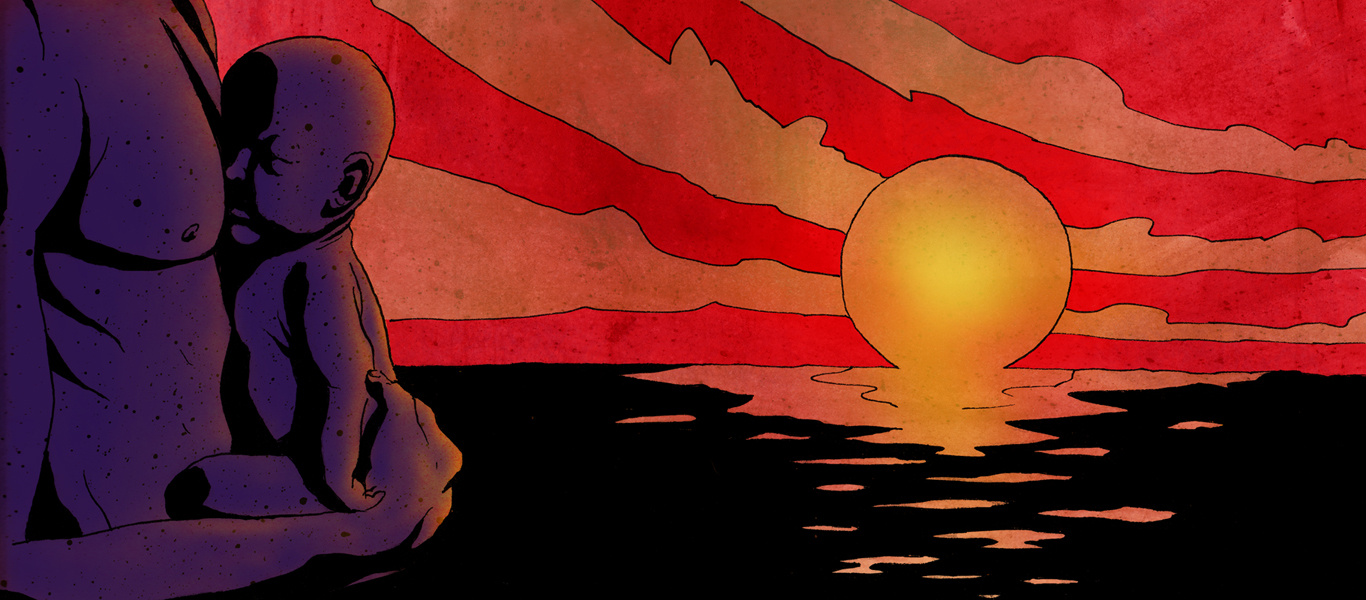

Tonight, they dig a second pit on our beach. Big men, all of them, dark hair and skin slick with sweat. Hands slippery on worn shovel handles. Feet bare, soles scorched and cracking. The sun is a glowing boulder buried deep in the ocean, still baking the sand from below the horizon.

For two days, relentless heat. For two days, the grass mattress in our room was a bed of coals. For two days I laboured, but could not get up. Exhausted, I could hardly breathe. Now I stand, finally cool in the shallows. My curls are matted from struggling, from useless pushing and straining. Salt drips into my eyes. My white linen shift is soaked, transparent. It does not flutter in the sea breeze.

There is my Tito, twelve feet away, up to his knees in the hole. The full moon limns his shaking arms, flashing silver like the blade of his shovel. The others have taken a break, dropped spades to catch their breath. Crouched between my husband and a smouldering fire, the men clear away unearthed rubble. Stones the size of an infant’s skull are pilfered from the dirt, added to a pile turning red in the embers.

All are shirtless. Three uncles are pocked from neck to waist; two are still too young to have known a woman. My Tito’s chest is broad and smooth, not yet scarred by the suckling’s spitting fat.

He will not stop digging until his heart and the ground are level. On and on he goes, though his braids and his smile have long since unravelled. He heaves rocks, heaves sobs.

I thought him stronger than that.

You look as empty as I feel, I say. For the first time in months I can see my toes. I am lighter than smoke. My swollen belly, deflated. You’ll barely recognise me now.

Wind moans from my throat, shrieks through the palm trees. Stiff leaves rattle with ancient bones.

Tito hesitates, expression haunted. Immediately his brothers haul him up by the armpits. ‘That’s enough,’ they say when he tries to climb back in. ‘We’ll run out of time. The hours are short before dawn.’

The uncles are fierce: they will drag him by the heels if they have to. Tito copes on his own. It isn’t far. Our village will always be close to the water.

Up the slope, rattan flaps slide open. Warm light spills from our huts, lean yellow fingers clawing over the dunes. Shadows flicker, strobing the beams. Women pass in and out of low doors, carrying bowls and banana leaves and knives. They stack them neatly on the shore. Singing under their breath.

There is my mother, leading the pack, shoulders and mouth drooping. Red rims her eyes, red coats her wrists, red spatters her arms past the elbows. She carries my sodden nightdress. She wrings it out over the coals.

I drift closer.

Mama, I say. She winces as thunder rolls from my guts, a loud rumbling knell. Our straw huts shudder, roofs tremble at the noise. Inside, children wail in their beds.

‘Hurry,’ she tells my aunties, my grandmother. ‘Hurry. She seems to be getting weaker.’

The women set clam shell plates in a rough semi-circle around the pit. Six in all: one for every hour until morning. Each is filled with oil poured from hollow gourds, dangling from cords on reed belts. Wicks are sunk into the liquid, then lit with a brand from the fire. The matrons walk in each other’s footsteps, single file, leaving a thin trail that is easily whisked away with a broom.

I howl a gale as my mother, sweeping, vanishes. I cannot remember which way she went.

My storm subsides when the men reappear laden with goods. Large banana leaves to line the hole, held in place by a mound of fiery stones. Currants and pineapple and juniper go in next. Pungent steam billows up to the stars. I tilt my head, track its wafting path. It dissipates so quickly.

Tito returns, suddenly alone. He looks out, over my head, searching the waves for traces of gold. The sky is yet navy, white, black. Silver glints on his cheeks.

In his embrace, the swaddled roast. Tiny and grey and not wriggling. Ten plump fingers and ten plump toes, buttered to prevent charring. It cooks with a clean, healthy scent. Grease snaps and pops. Hour after hour, my husband leans over the pit, drains dishes of oil, silently suffering the splashback.

The knives are sharp, the meat tender. Tito carves, scatters chunks for the gulls. He does not focus on me. Not even once. They’ve taught him well. He must pretend I’m not here, though he has prepared this feast for my sake. The only meal we’ll share as a family.

Sunrise catches all shades, or so the ancestors say. But my husband fills me up, I am twice full. I have all the strength I need to run.

WRITTEN BY LISA L HANNETT

ILLUSTRATED BY RICH SAMPSON

—

Lisa L Hannett’s first collection of short stories, Bluegrass Symphony, was published by Ticonderoga Publications in 2011. In 2012 Midnight and Moonshine, a second collection co-authored with Angela Slatter, will be published.

If you enjoyed Lisa L Hannett’s Flash Fear and want to read more of her fiction, please consider clicking through to our Amazon Affiliate links and purchasing a new book today. If you do you’ll help keep the This Is Horror ship afloat with some very welcome remuneration.

Buy Lisa L Hannett fiction (UK)

Buy Lisa L Hannett fiction (US)

1 comment

Whoa, that’s intense Lisa.