Horror is back, baby.

The journey was tough, but as predicted, we are in a glorious horror revival. Publishers are recognizing it, film studios anticipate it, and bookstores have set aside dedicated space for it. Fans are giddy, and the haters can do nothing but stir it in their bitter morning coffee.

The real horrors of the world rage on, captivating our lives, propelling our darkest nightmares in the spotlight. When the world burns, horror creators take note, and tap into those universal fears to give their stories credibility, using their talents to amplify the screams of those of us most affected by inequality and injustice.

It’s widely recognized that current genre trends reflect our real world, and these trends are cyclic. If the pandemic wasn’t bad enough, nefarious forces have been infiltrating society in areas left vulnerable, eroding trust and sowing discontent. As the original Satanic Panic did in the 1990’s, this new panic is sweeping the world attacking race and gender to force the outdated notion of “traditional family values”. And we find, time and time again, those people behind the book banning—and in some cases, book burning—are the very people they are warning us about.

Perhaps if they read the books that scare them.

Perhaps if they read.

The factors needed to keep horror in the mainstream are a dedication to exploring the stories of cultures from around the world, expanding our expectations of what the genre can achieve, twisting tropes dynamically to challenge those expectations, broadening the scope of the genre to cast a wider net, amplifying marginalized voices in ways we’ve never seen before, and a commitment to deliver the goods fearlessly.

The good news: These things are happening right now.

Two areas that could use improvement are blending horror with other genres to reach further than ever before and delivering these experiences boldly. Now, surely some of you are thinking that there are plenty of stories that blend horror with other genres. Yes, we have science-fiction horror, horror-westerns, even those “adjacent” things such as horror-mysteries (formerly called supernatural thrillers). Science-fiction, fantasy, mystery, and Westerns (though not as much as in the 20th century) are all recognized and respectable genres. Critics typically don’t like it when creators blend those genres with horror. They roll their eyes at it, pinch their noses shut, and purposely omit any mention of horror in their reviews and analysis, focusing on the other genre.

The respectable genre.

Well … it took a long time for science-fiction to become a respectable genre, and there are still those snobs out there that question its legitimacy to this day. Same for the fantasy genre, even when they ironically recognize folklore and myths from around the world as classic literature. God-forbid anyone ever writes something just for the fun of it.

Folks, I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: Sometimes, the blue curtains are just blue curtains.

One genre blend we don’t see too much of is horror-romance. True, most good stories are actually love stories, but the romance genre, the most popular and best-selling genre, yearns to play in other sandboxes. We’ve all seen the story of the horrifying monster, feared and dangerous, but also misunderstood, and in desperate need of a loved one’s touch to temper the flames of hostility. There’s some mileage left in that trope, but it will take the right creators to bring those stories to life for the modern age.

And to address the inevitable pushback from those old horror hounds gripping their DVD of Cannibal Holocaust, lamenting “there’s no romance in horror!”, um … yes, there is.

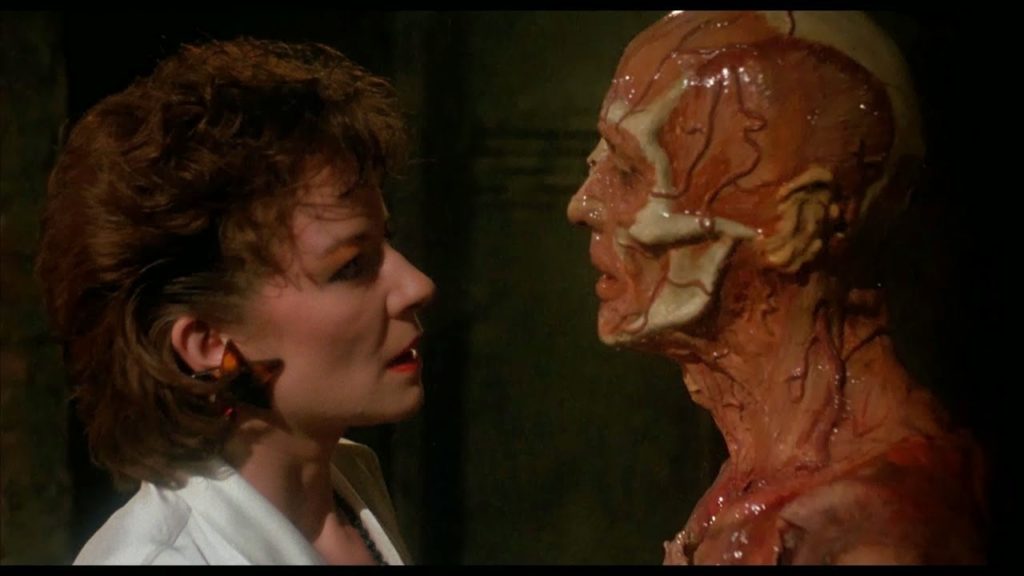

What do you think Clive Barker’s Hellraiser is, with Julia’s journey into forbidden love with Frank, proving her unwavering commitment to be reunited with him fully, even if it means damning her soul?

Those are the kind of stories we need to see. Sure, there’s room for angsty teen-oriented stories such as Twilight. But I also think if the Twilight series was to be remade today, the story would be much darker, somewhat akin to the vision of the rumored new True Blood adaptation. Romance is at the heart of those stories, and you must admit True Blood was actually pretty damn good.

Every single person on the planet has experienced horror, in one form or another, some more than others, and those experiences are tempered by the cultures and lifestyles of the creators. Unless we want horror to be a retread of the same tired tropes over and over again, it is imperative that we support these voices if the genre is to weather the storm of opposition. If horror could be measured on a sliding scale, with dead center being plain-old vanilla everyday horror, then we need to move the slider away from center into the danger zones.

Horror is not a dirty word, but its survival requires a down and dirty approach.

We need to create fearlessly.

Every single “classic” horror novel and film in the past one hundred years sprung from the imagination of someone creating fearlessly. The unholy trinity of novels which opened the doorway for modern horror—Rosemary’s Baby by Ira Levin, The Exorcist, by William Peter Blatty, and The Other by Thomas Tryon—resulted when the authors grabbed their idea by the reigns and pursued it to the end. They executed their stories confidently, unwilling to compromise their vision. Their stories were so captivating, so thrilling, that publishers willingly let these writers “go there”, breaking boundaries and barriers that shackled previous writers. They twisted tropes and warped expectations, and became the standard, setting the bar for horror fiction very high while scaring the hell out of readers even today.

Before the horror boom ended in the late 1990’s, we saw new writers pushing the boundaries even further. Clive Barker’s Books of Blood took the world by storm, as well as his film Hellraiser, burning the plans of traditional horror with horrific and ultraviolent flair. Kathe Koja’s The Cipher opened the Dell Abyss line and gave writers another outlet for fearless exploration, proving that sometimes horror doesn’t need a reason, that the unknown is the scariest thing of all.

Today’s writers face so many obstacles. A quick scroll through social media reveals readers not able to grasp fiction isn’t real, or authors are not their characters, and all horror writers are demented Satan worshippers. Then there are those that don’t want the horror to be scary, or that it was too scary, or the villain was too “villainy”. Sorry to disappoint you, but horror is often about shitty people doing shitty things for even shittier reasons, and sometimes those things are extremely scary. Maybe that kind of horror isn’t for you.

Beyond the back flap of the book, there are content warnings so readers can see if there’s anything in the book that could potentially be harmful, especially for those suffering from trauma and PTSD. Most writers don’t want to push their readers to relive their own personal nightmares unless the reader is comfortable doing so. This isn’t a form of censorship, it’s a way for writers to make readers fully of what’s in store for them without spoiling the story for those that want the experience.

We enjoy horror because it provides us with a safety net to escape real-world fears. People often talk about the social commentary found in science-fiction and fantasy, and while those points are valid, it would serve us well to remember the original social commentary came from horror fiction. The scares found in folklore and legends, even fairy tales, springs from the cautionary, warning us of the dangers of investigating the unknown.

You were warned about the witch in the forest, yet you still knocked on the door.

Writers are free to take that kind of tale in whatever direction they choose. That’s the beauty of the genre. It ranges from lighthearted horror/comedy to demonic end-of-the-world chaos and all shades in-between. Yes, there will be blood, and characters you love will die. It can be as fun as the original Fright Night, or as nightmarish as Hereditary. The best way to combat the negative is to write what sets your heart on fire, overcome your apprehension of disappointing your readers, and to write fearlessly. The next “Clive Barker”, the next “Kathe Koja”, will be the writer who connects with readers with a willingness to take them outside of their safety zones into unknown and dangerous territories, and to execute those stories with the confidence of someone determined to scare the hell out of you.

The horror genre can cast a wide net, and there’s room for every kind of story for readers and audiences to enjoy. The only requirement is that creators make their stories scary while acknowledging the volume knob turns from one to eleven and all points in-between. Horror still isn’t a dirty word, but creators are going to have get their hands dirty to keep audiences coming back for more.

BOB PASTORELLA