I was definitely wrong about that.

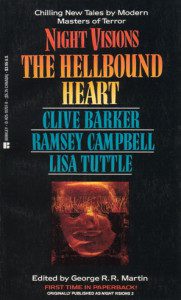

The Hellbound Heart, for the uninitiated, is a novella by Clive Barker, concerning one Frank Cotton and his search for eternal pleasure. It is a long novella, structured as a novel, with chapters and sections within the chapters, but it is not a short novel, that distinction typically reserved for more complex stories with concrete subplots. The Hellbound Heart deals with the results of singular plot, and sees it through to its bloody conclusion. The story should be familiar if you’ve seen Barker’s film Hellraiser, but that’s where the familiarity ends. If you’ve never read the novella, fearful that it is just a retread of previous material, then have no fear. Trust me, I thought the very thing myself, and couldn’t have been more wrong.

I remember when I first opened that book. Reading is ritualistic for me, so I have to start at the beginning, even with collections. Especially with collections. I imagine most editors order the stories in a specific fashion, and it’s fun to decipher the rhyme to their reason. Besides, I was really after the Campbell stories at the time, and fortunately they were at the beginning. And the stories were great, specific pieces chosen for his early Lovecraftian vibe. I guess I couldn’t help myself. After reading a few of the Campbell stories, I carefully marked my spot and skipped to the end, hitting those first lines of Barker’s tale.

So intent was Frank upon solving the puzzle of Lemarchand’s box that he didn’t hear the great bell begin to ring.

At that point, you could say the Cenobite hooks were set. I’d seen the movie several times by then, so of course I knew what box he was talking about. And here he was, starting the story with the box.

The Box.

Twenty-six years later, nearly 30 years since the story was written and first published, I decided to revisit the novella, primarily to gain knowledge and insight in writing novellas of my own. I learn best by example, and The Hellbound Heart provides one of the clearest examples of a novella done right in any genre. From my own recollection, this recent read was my second with the story. Blessed with both a fairly decent retention and wicked imagination, I find my memories of lines and scenes sometimes morph into something altogether different when rereading a book. Fortunately, Barker’s words were as scarred on my brain as the hooks and leather ornamenting the Cenobite’s flesh. The story is just as I remember it, though the Hellraiser film’s cast inhabits the character’s bodies in the book, spoiling my mind’s eye of filling in the blanks Barker deliberately left.

Back to The Box. Barker wastes no time, getting into the meat of the story in the first chapter. Frank’s attempts to open the box are quite sensual, working on the box feverishly, finding fresh alignments of fluted slot and oiled peg. Peculiar word choices here, but considering Frank’s character, a hedonist sexual adventurer, the descriptions fall into a sort of exotic wooden puzzle erotica, which is exactly how Frank would have thought of the puzzle. Upon solving it, he expects a doorway to open, allowing him entrance to a world of delights, with oiled women, milked women; women shaved and muscled for the act of love… and instead, he comes face to face with the theologians of The Order of the Gash. The Cenobites are described a little differently from what we see in the film, but their purpose remains the same. Strangely enough, the Cenobite we commonly call Pinhead is not named in the book. I’m still uncertain if Barker cast the Cenobite as female by saying it’s voice was light and breathy—the voice of an excited girl. Barker seems to have purposely excluded the Cenobites biological sexual orientation, and rightfully so, because it’s not important here. What is important is what Frank expects from them, which is vastly different from what he receives. I can’t help but think The Stones were right: “You can’t always get what you want… but sometimes you get what you need.” Poor Mr. Cotton’s soul is already damned, and he knows it. The Cenobites heard his call, and just pushed him into the pit as he wished. Frank seeks pleasure, and just his luck; the Cenobites speak that language quite well. The pleasure the Cenobites deliver, a synaptic pleasure overload, crossing the line into eternal pain and misery, is exactly what they feel Frank needs.

After the Cenobites deal with Frank accordingly, the story moves forward in time, and in context as well. Originally, I thought the novella was written in the very common 3rd Person Multiple Narrator perspective. Keep in mind when I first read this book, I finished it in one two-hour sitting. I’m a much more analytical reader now. This recent read took me about three nights, about two hours a sitting. I read it again with a purpose, trying to learn as much as possible from the structure of the book. And it was at this second part during this read that I realized Barker wrote this story from an omniscient, all-knowing narrator. This may not seem as much as a revelation for the normal reader, but its implications allow quite a bit of insight into the deviousness of Barker’s style. By slipping in and out of each main character’s mind, we get a scene-by-scene view of the action of the story by the character doing the most harm to the others. It’s also worthwhile mentioning, without spoiling too much of the story, that Kirsty is not Frank Cotton’s niece. She is a friend of Rory (Larry Cotton in the film) Cotton, Frank’s brother, and is somewhat jealous of Rory’s wife Julia, and with good reason. There’s a subtle nuance here, but Kirsty aims to hurt Julia by informing Rory of his wife’s philandering. Kirsty is a sweet girl, but a little clumsy, and certainly not admired by Julia, who finds her rather droll and annoying. After Kirsty happens upon Julia, and watches the painful truth, Kirsty feels she has a duty to her friend, Rory. Yet, for once, she will finally have the upper hand against Julia. Of course, things don’t go exactly as she planned.

There are very few actual lines from the book that made it into the film. Of course, Pinhead’s iconic words are there, possibly said by yet another Cenobite in the novella; Barker doesn’t make it very clear with the description of the Cenobite, but it’s fun to think it was the bejeweled Hellpriest. When I first read those words, it was like finding a very cool Easter Egg in a film or video game. Reading the story again, I found even though the words rang of that cool familiarity, there is this sense Barker carefully chose those phrases, that even if the story was never made into a film, those lines would still fill the reader with dread. Simple words like tear, and soul, hit at the core of our humanity. If we all eventually leave this mortal coil, then for most of us, it is paramount we enter the afterlife with our souls intact. The Cenobite’s threat strikes at the very heart of us, and those words still chill me to the bone.

The book came out during horror’s splatterpunk years. Focusing on the extreme, with gory details and transgressive characterization, The Hellbound Heart spearheads the genre. Reading it again today, with a much more mature mindset, attempting with much difficulty to remain as analytical as possible, I find the story has transcended the genre. Even when I originally read the story, it didn’t feel like splatterpunk. Maybe then I thought of it as splatterpunk lite, with pretty writing. Now, the story reads as literature.

So what makes this particular story fall into literature? The words and descriptions Barker uses aren’t much different from anything else he was writing at the time. I think the story is very difficult to fit into any single sub-genre of horror. It’s not a vampire tale, though Frank’s return is dependent on blood, and lots of it. It’s not a ghost story, as Frank is a physical entity. The mythology of Hell is fresh and fiendishly human in its depravity. This is not just any old blood and guts story. The Hellbound Heart is, at its very heart, a fable, reminding us that some things are best left alone, and that even our deepest desires can become our greatest defeats. Those are not the themes of some cheap dime store toss-off. Barker took our fears, our sins, and paraded them front and center, and the reason we like it so much is because it’s just like looking in the mirror with a safety net. That’s literature, folks, and that’s what makes this book a classic work in modern horror fiction.

Did I accomplish my mission? I reread this book originally with an analytical mindset, hoping to make some connections with structure and format of the novella form. The answer is both yes and no. I thoroughly enjoyed rereading this book, and found myself backtracking every other page to make a note of how Barker achieved his effects. Well, I backtracked for at least the first twenty to thirty pages. After that, the story sucked me in, and I found myself lost in the pages.

Yes, twenty-plus years later and Clive Barker can still give me nightmares.

Regardless if this is your first time, or tenth time, please take the time to read this classic horror tale again.

Mr. Barker has such sights to show you.

BOB PASTORELLA

If you enjoyed this and want to read The Hellbound Heart please consider clicking through to our Amazon Affiliate links. If you do you’ll help keep the This Is Horror ship afloat with some very welcome remuneration.

Buy The Hellbound Heart by Clive Barker (UK)

Buy The Hellbound Heart by Clive Barker (US)