Michael David Wilson and Clay McLeod Chapman

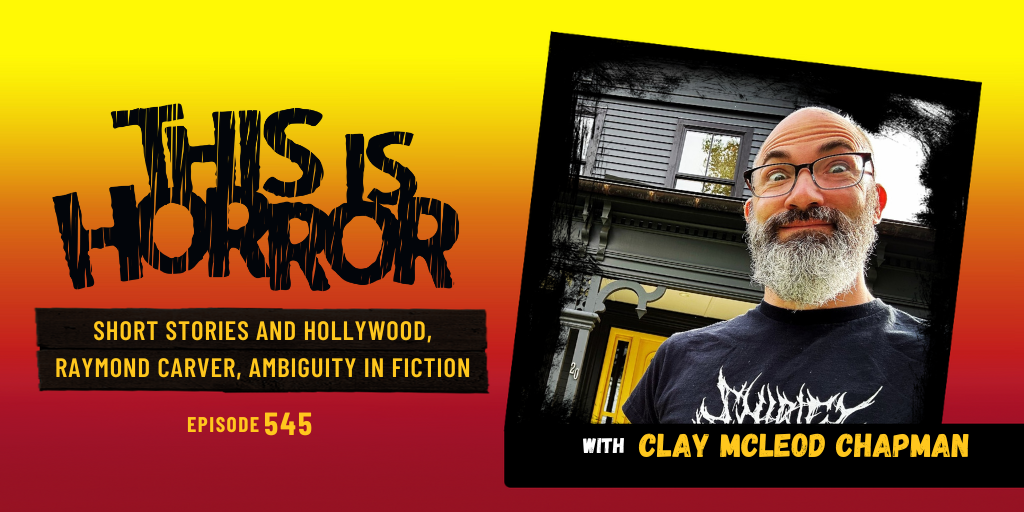

TIH 545: Clay McLeod Chapman on Short Stories and Hollywood, Raymond Carver, and Ambiguity in Fiction

In this podcast, Clay McLeod Chapman talks about short stories and Hollywood, Raymond Carver, ambiguity in fiction, and much more.

About Clay McLeod Chapman

Clay McLeod Chapman is the author of the novels What Kind of Mother, Ghost Eaters, Whisper Down the Lane, The Remaking, and miss corpus, short story collections nothing untoward, commencement and rest area, as well as The Tribe middlegrade series: Homeroom Headhunters, Camp Cannibal and Academic Assassins.

Show notes

Thanks for Listening!

Help out the show:

- Support This Is Horror on Patreon

- Listen to This Is Horror Podcast on Apple Podcasts

- Listen to This Is Horror Podcast on Spotify

- Rate and review This Is Horror on Apple Podcasts

- Share the episode on Facebook and Twitter

- Subscribe to This Is Horror podcast RSS Feed

Let us know how you enjoyed this episode:

- Leave us a message on SpeakPipe.

- Write a comment below.

- Connect with us @thisishorror.

Resources

- Buy Clay McLeod Chapman Books

- Watch video versions of This Is Horror Podcast conversations on YouTube

Podcast Sponsors

House of Bad Memories by Michael David Wilson

From the author of The Girl in the Video comes a darkly comic thriller with an edge-of-your-seat climax.

Denny just wants to be the world’s best dad to his baby daughter, but things get messy when he starts hallucinating his estranged abusive stepfather, Frank. Then Frank winds up dead and Denny is held hostage by his junkie half-sister who demands he uncovers the cause of her father’s death.

Will Denny defeat his demons or be perpetually tortured for refusing to answer impossible questions?

House of Bad Memories is Funny Games meets This Is England with a Rosemary’s Baby under-taste.

Buy House of Bad Memories from Cemetery Gates Media

Buy the House of Bad Memories audiobook

The Girl in the Video by Michael David Wilson, narrated by RJ Bayley

Listen to The Girl in the Video on Audible in the US here and in the UK here.

Michael David Wilson 0:28

Welcome to This Is Horror, a podcast for readers, writers, and creators. I’m Michael David Wilson and every episode, alongside my co-host, Bob Pastorella we chat with the world’s best writers about writing, life lessons, creativity, and much more. Before we get into today’s conversation let’s have a quick advert break.

Bob Pastorella 1:01

House of bad memories. The debut novel from Michael David Wilson comes out on Friday the 13th this October via cemetery gates media didn't he just wants to be the world's best dad to his baby daughter. But things get messy when he starts hallucinating his estranged abusive stepfather Frank, then Frank winds up dead and Denise held hostage by his junky half sister, who demands he uncovers the cause of her father's death with the need to feed his demons or be perpetually tortured for refusing to answer impossible questions. Clay McLeod Chapman says house of bad memories hit so hard, you'll spit teeth out once you're done reading it. Preorder house of bad memories by Michael David Wilson and paperback at cemetery gates media.com or an ebook via Amazon.

RJ Bayley 1:45

It was as if the video had on zip to my skin, slunk inside my tapered flesh and become one with me.

Bob Pastorella 1:54

From the creator of This Is Horror comes a new nightmare for the digital age. The Girl in the Video by Michael David Wilson. After a teacher receives a weirdly rousing video, his life descends into paranoia and obsession. More videos follow each containing information no stranger could possibly know. But who's sending them and what do they want? The answers may destroy everything and every one he loves. The Girl in the Video is the ring meets fatal attraction for iPhone generation. Available now in paperback ebook and audio.

Michael David Wilson 2:24

Today on This Is Horror, we are chatting to Clay McLeod Chapman. He is the author of novels such as ghost eaters, whisper down the lane, the remaking and Miss corpus. He's also the author of short story collections, nothing untoward commencement and rest area as well as the tribe middle grade series, home room, head hunters camp cannibal and academic assassins. His latest novel What kind of mother arrived earlier this year in September. And that is one of the reasons that we've got clay back on the show. So with that said, let us not delay. It is clay McLeod Chapman on This Is Horror. Clay Welcome back to This Is Horror.

Clay McLeod Chapman 3:26

Oh my god, I missed it. I missed it. It's been it's been too long. It's been what a year.

Michael David Wilson 3:32

Yeah, it's been a year. And and what a year, then. Yeah, yeah. Well, I mean, that's what I want to talk about, actually. So the last time we spoke, it was the summer of 2022. So what have been the biggest changes for you both personally and professionally, in that time,

Clay McLeod Chapman 3:57

oh, my god, um, personally and professionally, I, you know, I, I don't want to be glib, but like, I do feel like everything is feels so kind of chaotic, and a bit of a you know, the, in our household, it's, it's, it always feels like a bit of a whirlwind. I'm gonna murder my weather metaphors all night, just so so you know, but I don't know, like, I have two sons, and they they have become older. And as they grow, so do their foibles and their their kind of needs. And, you know, I guess like, you know, I'm trying to I'm searching for the kind of best answer. The biggest kind of change, it isn't so much that kind of change as much as it's just kind of an evolution of of serve ival I am trying desperately to kind of keep everyone in our family happy and safe and healthy. And tell stories at the same time and somehow make a living doing it. And I don't know. Yeah, everything feels a little. Like, I think the volume just starts to crank up right, like the intensity of life and the kind of like, the anxiety and the fears, like everything just starts to kind of like, I don't know if it was that three before, and now it's seven, or 11 or 20. Like, everything just starts to with the metaphor, the frog in the boiling water. Oh,

Michael David Wilson 5:43

yeah. Yeah. And the frog is unaware. It's being cooked. Yeah.

Clay McLeod Chapman 5:49

It's only when you look back and say, Oh, my gosh, the water was a lot cooler. Last year. You know, some people have died. Some people. You know, like, it's, it's just funny when you think of like, a year, like you just do the cross section you like, kind of slice your life into a chunk. And you say, what was life like before this chunk? And you're like, Oh, well, that person was still here. I was, I was still friends with that person, maybe. I don't know, like, everything. I'm kind of being mealy mouthed at the beginning, which is embarrassing, but like, I don't know, like, I, I serve, I'm surviving. And I think maybe that's, that's maybe the biggest kind of achievement for you know, nobody hates each other yet in this family.

Michael David Wilson 6:42

Which is good. You know, because there are a lot of families where there are rivalries, there is tension, there is hatred. And if you get to that point, it's then so much harder to kind of go back or to fix it. So it's better to not get to that point. To begin with.

Clay McLeod Chapman 7:03

It's so I don't know, like, I feel so maybe it's not an embarrassment, maybe it's a little bit of like, like lavender shame, pink shame. Like it's like light, like a light, huge shame. Where I, I've been listening to so many, like, when I think of like the show, and our interviews, like I want to, like, I always want to come with my best foot forward. And yet somehow, I inevitably, like just, I feel like I fumble in a hopefully a charming way. But it's it's always that feeling of like, wanting, you know, you know, when you like, are entering the stage, and you're like, Okay, what it's going to be like, I'm going to do this, I'm gonna say this. And then the second the curtain rises, like your shoelaces untied. That's, that's my vibe of the moment.

Michael David Wilson 7:54

Yeah, yeah. But I think I mean, really, it's a glorious metaphor for life. And indeed, for story writing. I mean, we can have this plan, we can have this great idea. But then inevitably that there is fumbling, there is awkwardness, there is imperfection, but that makes it authentic and real. And I kind of think if it was polishing, seem to be curated. In a sense, it would be artificial. So you've given us the realism.

Clay McLeod Chapman 8:31

I think that's all we've got right now. Yeah. I, and maybe this is a terrible segue. But like, I feel like there's like I've been thinking a lot about the the kind of AI of it all the kind of conversation about what, what separates us from the machines. And, like, I the only thing that I can think of personally is that idea of like the kind of rawness and the the kind of the the clumsiness to it, that kind of the imperfections of either our writing or whatever the art itself is, that makes it feel all the more real, or at least makes it feel the most like you that like, I don't, I'll never make something that's perfect. And it's just, you know, a fire my stuff tends to be kind of a far cry from but like, there's at least this kind of desire to like, achieve a certain rawness or a certain kind of like, like, tap, tap of, like a specific like real emotional note. And that that's something that I don't think, you know, artificial intelligence can do. And it almost feels like it's kind of Giving me personally like a little bit more permission to be kind of rough around the edges and a little bit more imperfect. I don't know, like, I feel like probably every other 99.9% of the authors who you would talk to would say, they, like, we're striving for that perfect sentence or striving for that perfect, like, Booker thing. And I almost feel like I'm kind of retreating in the opposite direction of just like, hey, man, like it's, it's a little more loosey goosey. And that's a, that's all. That's all I got, for better or worse. And

Michael David Wilson 10:41

so many directions that I could take this conversation in both with what you said there and what you said a few minutes previous. But I mean, in terms of this idea of perfection, I think when we're younger, particularly we do strive for perfection. But then as we get older, we hopefully realize that perfection is an illusion, it's a fallacy, you can't reach perfection. And, actually, I mean, if you look at human beings, and you look at art, there is perfection within the imperfections. That is what makes somebody perfect, you know, if we're even to use this flawed language. And I think when I realized that not only do we not necessarily have to strive towards perfection, but we need to understand that it can never be attained, we can never reach it, there's a kind of freedom. And I think it enables you to let go of stories easier as well. It's like, well, this, this isn't perfect, but this is good enough for this is finished for now. We send it to to the next stage and and see what happens. So I mean, that that's kind of one strain of thought, from what you've said. The other it brings to mind, what was said when we were speaking to Chuck Palahniuk, and there's almost a reaction against AI and against perfectionism, that you're bringing imperfection to the work intentionally. So sometimes he's putting intention or errors in the text to see who picks up on it. And the magic of that is if you deliberately become known to be putting these imperfections in, then when you make a mistake, people don't know, was that deliberate? Or did you actually do that intentionally?

Clay McLeod Chapman 12:50

Yeah, that's amazing. Little little easter eggs of imperfection. I love it. I would be so lucky to like, like, intentionally make a mistake, when I make plenty of them kind of all, you know, unintentionally. I think the problem was, like, I read, I like picked up the road recently. Um, you know, like, I think the road is such a by Cormac McCarthy. I think it's an amazing book, it's probably one of the most affecting books that I've read in decades. And, you know, I It's like one of the only books that I like, occasionally reread, I think there's like two or three books that I'll just like, it's time to read this book again, and see if I can kind of like mine something new from it that I hadn't before. And that book has such an economy of language that I I imagine and I have not I have read zero Cormac McCarthy interviews, so I don't know if this if there's any truth to this, but I believe I have to believe that he agonized over every single word that like, you know, one sentence took a day to craft to fashion and you know, it's wholly inappropriate to compare oneself you know, to put yourself on the scales against someone like Cormac McCarthy but like, I do feel like when I agonize over sentences, and like, like, just try desperately to fashion the right phrase or the perfect sentence. It comes off sounding so artificial are so kind of like process. There's like a certain kind of like prefab fiction quality to it. But if I can, in lieu of spending that time agonizing over a sentence, reach the emotional court, like reach the like, kind of like strike the nerve. Mmm, that feels, it can be raw, or whatever the kind of delivery system for that emotion can be imperfect. But it still hits the cathartic point or it still hits, hits whatever the target is. That's, that's my hope of the moment, as I loosen myself up a little bit and get a little more unraveled. In my, my writing process.

Michael David Wilson 15:28

Yeah, and I think too, I mean, coming back to perfection versus imperfection, sometimes, a more imperfect or in exact sentence can be what is required in that moment of the novel. And eventually you put a kind of Cormac McCarthy style sentence in it would, it would ring false. So actually being perfect would be imperfect for the novels. They were. We're kind of creating a paradox here. But I, I think, we have a sense of tone and what is and what isn't stylistically and aesthetically, right from each novel. And so I mean, if I think of the novel that I recently put out that you were kind enough to blab so thank you very much for that house of bad memories. If I were to put a Cormac McCarthy style passage, while Jade, the junky stepsister was having a rant, her useless boyfriend Gazda. It probably wouldn't ring true, like, hang on what what happened here? What's going on?

Clay McLeod Chapman 16:43

Um, I mean, do you feel like with your writing, like, do you do you spend the time? Like, is it the occam's razor of like, what gets me? Like, I'm telling the story, I'm navigating the narrative, as opposed to I am luxuriating in the pros. I'm like, like, drifting through the sentences. You know, I, I, I'm curious, like, Do you have a process that kind of sees you through from from project to project story to story, book, the book.

Michael David Wilson 17:22

So of course, we've booked two books, some will inevitably be easier than others. But the typical process is that I will plan out a story before I write anything. And it will be a plan where I loosely know how it's going to start. I know the beginning. I know the end. This is where it as much variation from project to project because some are almost have attempted to camp to break down. Whereas others, it is going to be like, Look, this is a start. This is the middle, this is the end, I don't know exactly what's going to happen in the journey. I know where I'm going or vaguely where I'm going with each point. So I guess there's these things that we can center on to, to at least make sure that I'm going there. But, of course, the other problem that I find is even if I kept a bite, yep, to plan it out. Then in the first draft, it's like, oh, well, this little root, this little side mission looks like a good idea. So then that can completely change the trajectory or the idea of the story. Yeah, because I've got one work in progress where it, it was planned out chapter by chapter. It was going to be far more commercial than anything I've written. It is a kind of Adrienne Lin inspired psychosexual thriller. But then there was just a character, a quirky character appeared, and it made it way more weird and bizarro, and it just took us down this weird rabbit hole with a calisthenics sex coach, and his like, I think it's because, like, I have this idea of, Oh, I could write something commercial. And that might be good for my career. But it's like the reason that I got into this was was almost like to scratch my own creative edge and to have fun and, and to do things that I didn't get interesting. And so yeah, it's like this constant battle that I'm having. And with that story, I've just got to write out every bit of it right now and be like, Okay, what is the story that I actually want to tell? Because I feel that I'm telling Three different stories now and I need to tell you no to maximum, but probably one would be, would be better. But you know, after that I mean that the first draft, the first draft is just telling a story, getting something down. Then the second draft is me putting on a more editorial hat and me thinking, okay, how can I like tell it coherent story? How can I sort of conform to story structure or make intention or choices to not conform, delay, notice a lot of things and have some bad memories where they would not advise you to do that, particularly some of the prolong Tarantino as conversations, but it's like when I'm making it a deliberate choice to not conform here. And then the third draft or the third stage, that is when I am going over every sentence, every little detail. So even though like some people might be surprised, because it's not, this is not like Cormac McCarthy style writing. But I have really thought about every sentence, I have really gone over each detail. And of course, when it's gone through those three drafts, so there's three stages, then I send it to an editor or publisher or a beta reader. And then their feedback, it can mean that the whole thing is reshaped again. Yeah. And then, like I am very meticulous. So that will mean that it goes through the three stages. Again, if I've changed the structure and the dynamic, then I also have to check every single sentence. So it is a long process, but it seems to be the one is working for me.

Clay McLeod Chapman 21:56

That's great. Just discovering your own process. Like regardless of whether it's the same for book for book like, I don't know, man, like just just the idea of navigating that discovering that like I yeah, I feel like it changes book for book, right? Well,

Michael David Wilson 22:17

yeah, that's a quote, and I'm not sure who it is that it's attributed to, but you don't discover how to write a novel, you discover how to write the novel that you're writing. And that changes every single time.

Clay McLeod Chapman 22:33

Can you imagine, I swear to God, like, I don't know, you want to create these little little baby beasts, right? Like they they are their own, you know, organisms, and they, they're never going to be the exact same thing. They're never going to be perfect. And they're all going to have through nice little I don't know, like, like, it's like a hand carved box, right? Like you're Yeah, want those imperfections, those those kind of like nicks and kinks to be a part of, of what what makes it what it is? Yeah,

Michael David Wilson 23:05

yeah. Well, I'm having an interesting moment with the novel that I've just started. Because I would say that the first two books that I put out, the writing came quite easily they would these stories that just kind of worked in the composition. Whereas a lot of things that I've written since, and of course, it could tie in to my personal situation, which longtime listeners will know about. And I spoke a little bit about whether you are fair. So it's been a tumultuous time. But I have found the last two or three stories, my novel length stories that I've written, they've become more complicated, the writing has become more difficult. And it's like, goodness, what, what is going on here? But actually, so I've been screenwriting recently, and I adapted one of my short stories into a full length movie. And because I had expanded that story, I know, you know what, I think? I think what was originally a short story, could be a book. So for the first time, I've adapted a short story to a film and now I'm adapting kind of both of them into a novel. But because I've got all these pieces and because I know this world so well, it's so easy to write. It is such a joy and this doesn't happen every time I mean it's gonna be different for different writers maybe not comes along, whatever every five books I've read 10 books, I don't know but this one is Very easy. So I'm just enjoying it. I'm thinking what, what a moment? And, and it's also got me thinking, is this a weird new process is, is this a bizarre way I come up with a short story I turned into a movie and I turn into a novel is not a normal way of writing, but you kind of have to do what works for you.

Clay McLeod Chapman 25:29

Not to get businessy. But, I mean, it's, it is interesting how folks in Hollywood are very attuned to the idea of short stories being, you know, seeds for features. So, a lot of times, you know, you know, folks will reach out and be like, hey, you know, got any short stories, or you should write a short story, because we can turn that we can adapt that into something. And it, it's, it's, maybe it's a little cart before the horse, but like, it is this, this kind of like, this process of development, where, you know, a producer will, will want or desire a, you know, the ultimate goal for them is like, let's make a movie. But we have to have a script, we have to have a story, let's, let's, let's kind of plant the seed into something where we get a fiction writer to, you know, draft, like write, write a short story. And that short story is, is kind of generated as a means to become something else. So they've already kind of like, you know, I'm cringing at myself for saying this, but like, in the era of content, that, you know, something that will always have the intention of being a film is born by being born out of like, another medium, but it's, it's, it's a short story, or it's, it's something else. And I don't know, it is, it is an interesting kind of, like, way of going about it. And, you know, maybe I feel like stories or stories, and regardless of the medium that you tell them in, it's always nice to have a story kind of dictate what medium it wants to be in. And I always I occasionally get it wrong, where it's like, oh, I want to write a short story, or oh, I want to write a book. And then like, somewhere along the way, it'll be like, Oh, this is actually this doesn't want to be a short story. This wants to be a comic, or that wants to be a screenplay, or it just wants to be something else. But it took that kind of initial, you know, journey to kind of figure out what it actually needed or wanted it to be.

Michael David Wilson 27:53

Well, I mean, it occurs to me that you haven't answered the very interesting question that you gave me. What do you what what is your typical, if such a thing exists? novel writing process? What does it look like? For you? How many iterations does it go through before you show it to someone else?

Clay McLeod Chapman 28:14

I mean, I'll answer the latter first, like, I I'm, like, extremely dependent on feedback. Like I find myself needing BETA readers pretty early on in the process, much to the chagrin of anyone who I ask to do it, because it's usually really raw and rough and slabby and not so put together. But, uh, I, I need to kind of ask the question, like, what is this? Like, what, what have I done? And, you know, because I find when I answer that question for myself, like, Oh, I've done this, and this is, this is clearly what this thing is, like, I have no friggin clue. Like, I I'm always wrong. When I kind of answered the question, what is this? And like? And definitely more recently, like, I stopped asking myself that question, because like, you know, I usually, if I answer it for myself, it tends to be either wrong or way off base. But if I can have that conversation with a beta reader, and I can say, I've done this thing, I don't know, what it is, helped me like, What is this? And then that discussion with that beta reader, like, I read this thing, and I feel like you're kind of getting at this or maybe you're doing this, like, it kind of allows a certain kind of understanding that kind of take place for me. And I'm like, Oh, okay. Now, you know, and it's usually very macro. It's very general. It's like it's the it's the kind of big picture kind of questions as opposed to the kind of like Line edit kind of like, let's get granular. Like I just love those kind of larger talks upfront with beta readers. Because it kind of informs me to what I've been doing. Because more often than not, I'm the last to fucking know. And I kind of love that, like I, I love. I don't know, like, I I'm just letting go of understanding or even kind of answering the questions for myself because I just feel like, my answer is just so not important. So not worth it. So not like. And that's so counterintuitive to everything I feel like we've been told or taught or trained. And, frankly, I see other authors, and I believe that they know, I believe they answer that question for themselves and that they know. And that that's right, that like, you know, I have this isn't like I think I like someone like Paul Tremblay, and, and I love his writing. I feel like he has to know what he's doing. Because how could it be? Like, it's just like, it is, it is astounding what he does that like, I have to believe, I want to believe I want to I just want to just believe that he knows exactly what he's doing at every step of the way. And if he doesn't, I don't know if I need, I want to know that that's true. Like I like it's safer for me to know, or assume that he's in control of his writing. Because I am losing control of my writing. And I feel like that is the process right now I am embracing the chaos in this way that like it will lead to and it will hopefully lead to a discovery for something better, or grander than maybe what I had originally intended. Do you listen to a band called Animal Collective?

Michael David Wilson 32:28

Animal Collective that the name sounds familiar, but I'm I'm blanking.

Clay McLeod Chapman 32:35

I don't, I'm not necessarily recommending them. But I love them. Actually, maybe I should count. I love half of them. Half of their music to me is euphoric. It's just revelatory, like it is the best, most amazing, life affirming music that I ever listened to. And the other half is just dreck in my personal opinion. And that's so that's so bad to say. Because I like, but I think that's what I love about them. That like they they are chaos. And it's like, I feel like they kind of go to metaphors like It's like jazz man. Like, it's like, you know, you're like freeform in it. And then all of a sudden, like you hit a certain kind of rhythm or a certain kind of groove. And like now it's like the jam. And it's like the jam band. Like, you know, like, it's like freeform freeform. We're kind of loose, we don't know where it is, we don't know where we're going. We're you know it, we're kind of lost at sea. And then there it is. There's the threat, we got the thread. And now we're picking it up and picking it up. And it's like, and, and that is true. And I think that's what jazz is. But I feel like I've used the jazz metaphor a few too many times. So tonight, I'm going to use the Animal Collective metaphor, which is to say, here's a band that's kind of like one of these folk, funk, punk, in the kind of like just everywhere kind of things. And it's so loose and so untethered, and so unmoored. And it just sounds like noise until, like that rhythm kind of kicks in, or, like something kind of comes out of it. And you're just like, you know, you've been adrift you've been lost at sea for so long. And then all of a sudden, like, here's this, this kind of song that is kind of born out of that. And it's, you just, it's just phenomenal. Like once once they hit that moment, and it it's worth it, the whole journey the whole ride, because it's just all of these raw elements have been kind of building up to this this moment. This this kind of crescendo and it it's just, it's all inspiring, and I, for better, for worse, maybe worse. Like, have started to kind of write that way, where it's like, I don't friggin know, I don't know where this is going, I this is the like, this is the noise. This is the, the raw emotions that I want to play with. And like somewhere in there. There is a there's a rhythm that connects or like something, something kind of is born out of that chaos. And you just got to ride that wave until it manifests in actual tune or harmony, and then it becomes the song. And then it's like now now we're, we're planning. I just need 500 pages to find that 300 page book, right?

Michael David Wilson 35:43

Yeah, yeah. And I think it to write something good, you often have to break a number of rules to really write something that is going to resonate. But of course, the problem is knowing which of the broken rows you can keep in and which you have to absolutely get out. And as you say, I mean, you might go on a 50 page journey to get to the scene that you really needed. But it's like how much of this journey is exciting for the readers how much it is journey? Do we need to cast? And I mean that there are numerous times I mean, we've every novel that I write that will be chances are things that I do where I think, I don't know if I can get away with this. But literally me just delivering it to the beta reader not mentioning what it is I've done and seeing what comes back. And sometimes, you know, it will come back like why did you do that? Or? I'm not sure about that you should probably get get rid of it. Other times, no comment on it. Other times, this is the best part of the work. So I put these experiments in to see what happens. I'll keep things in sometimes that I free or oh, maybe I should cut a book because there's that doubt. Let's see what the beta readers say.

Clay McLeod Chapman 37:18

Yeah, yeah. No, that's, I mean, like, God bless the editors. Like I, if it's not the beta readers, it's definitely the kind of like, I've been really fortunate like the last, I have, I have two moms to two different editors, Rebecca and John Tay. And they, they are there, they're like, they're like moms to me, and they're like, oh, like we're gonna raise you. We're gonna figure out how to, like, put you into this world. And like, we've done this for going on five books. Now. We're on our fifth. And the process is always so chaotic. And so kind of like, oh, like, by the seat of our pants, but like, once, once the they kind of like, start kind of digging in with me. It becomes something it's not the kind of one like no one person, including myself is kind of like, responsible, culpable. Like, like, it's the kind of, it's the sum of all these different kinds of parts, you know, these contributors. I know, like, it's like, it takes a village to make a book. And I, I lean on my editors. Maybe too much. I don't know. You know, I'm sure they would have opinions on what the heck I'm doing. And whether I'm doing it right. But uh, you know, it's just so funny how it's interesting how I don't know, you go into this and you're like, here's this raw slab of just pure, straight up funky emotion. And we're gonna find the book in it, aren't we guys? Right? Right. You know? And, yeah, yeah. My, I'll shut up about this, I swear. But the go to story, and I'm going to get all the information and details wrong, so forgive me, but like, do you ever read Raymond Carver? Oh, yeah, yeah. I do you know that. Like, do you hear the story? Like, did you ever hear the story of like, the things we talked about? God, what's the name of the things we talked about when we talk about when we're in love in love?

Michael David Wilson 39:48

Yeah, yeah, yeah. When

Clay McLeod Chapman 39:49

we talk about love. I feel like the story the mythic kind of urban legend that I've been told is that he wrote those stories. Is and they were bigger, longer, more kind of flowy flowery or, and then his editor whose name I knew at one point and whose name I can't pull out of my head at this point which is embarrassing but there you go. Famous editor who did a lot of amazing edits for a lot of amazing authors took Raymond Carver's books stories, like just cut them, like just like nananananana and like just like whittled them down to the bone, like took all of that flowery prose out and just like, like, like, just like, just carve whittle that shit. And it became this this is the these are the stories as we remember them. And you know, apparently I think Raymond Carver was like, rah rah rah rah rah rah like this is how dare you like, you know, like really pissed that like that his editor, like how dare this editor do this to his work? And, but by whatever feet, whatever design, those books, those stories, were either published, intermittently, or we're kind of put out there. And people respond to that. They're like, This is amazing. This is like, and Raymond Carver had to be like, oh, like, like, kind of begrudgingly, like, Okay, fine. Like, and Raymond Carver became Raymond Carver, the Raymond Carver, we all know and love. To the extent where later in life, he was afforded the opportunity to republish a new edition of those stories, but the kind of director's cut version of it, like the, the, the way that he wrote them the way that he wanted them to be, and readers kind of responded to them like tepidly, like loot, like, like F, you know, like, not as not as good as the, the the first round. And I think there's this is that that kind of like, how telling is it that you can have like, you know, that like the the process of like, what we write as writers, like, we think this is what it is like, this is what it is like, No, this is me, this is my voice. This is my story. And an editor comes in is like, let's like, let's get rid of all that. That extra additional stuff. And it hurts. It's like so frustrating. Like you want it you want it that stuff in there. But like a great editor can kind of like know your story, almost better than yourself, or can help you discover that story kind of within that. freeform jazz, funky mess. The funky junk. Yeah,

Michael David Wilson 42:42

yeah, not so interesting. Because I mean, if I think about minimalist fiction, as is the case with a lot of us, then I think about Raymond Carver. So to find out that, you know, actually to begin with, that wasn't what he was writing, all and the fact that he became the father of minimalism was actually accidental. That's just incredible. And it now makes me wonder. So with the latest story is, Did he accept this role as it were as a minimalist writer? Or was the process the same every single time and, you know, he's added to his life? Why aren't you learning and going to cut this anyway? So that's, that's fascinating. And now, because I haven't, I want to read the expanded version, I want to not only read it, but read them kind of consecutively, and then compare them because that is just fascinating. Yeah,

Clay McLeod Chapman 43:51

I may I want to, I'd be really curious if someone's actually, if someone's listening to this now, whoever you may be. And you're, and you hear me tell, like, regale this Raymond Carver story, and you're like, that's not the way it happened, that it totally was like, He's got the whole story wrong. I'd be really curious if someone can kind of pin like, kind of lead us in this moment, to the right story, because I feel like it's so compelling. And like, maybe I've just taken like, I've overheard this story, and I've like, it's mutated and kind of like, evolved into this urban legend in my own head. But I feel like that's the story or like a very rough, slipshod version of it. And I want to know what I got right or what I got wrong, because I do feel like I remember like, the editor was like, no, no, no, we're gonna like, no, no, no, no, no. And like, I don't know what the decision making process was like, if, you know, Carver had to at some point, say, Fine, let's give it a try. Like we'll do your version of it and see how it goes. Which It is such a leap of faith for any author to take, like, I can't imagine, like, if I was so protective of my writing, and an editor was like, I'm going to take your stories, and I'm going to cut them down by a third by a half by a, you know, however much. And they're gonna, you know, like, like, that's, that is a huge leap of faith. And, and, you know, at some point, that trigger was pulled and Carver had to be at peace with it, maybe begrudgingly, maybe maybe at kind of extreme emotional duress. But to then be like, Oh, wow, people really do respond to that well, and then like to, because I think he was kind of a bit of an ego maniac. If I'm not wrong, that like he was given the kind of privilege to like, now it's now I'm going to do it the way that I originally intended it. And I don't know, the director's cuts are never as good as the well, am I gonna say that? Is that a real statement that I'm going to make? I'm going to take that back. Usually, sometimes more often than not, when we don't have the external factors, kind of giving us that friction or that tension? I think when all tours are kind of left to their own devices too much, without an extra pair it on their shoulder to be like, do you really want to do that? Like I think you should, maybe you should cut that those 50 pages don't need to be in the bow. It's it's left a little bit unbridled, unfiltered. Yeah,

Michael David Wilson 46:42

I wonder if the reaction to the director's cut for want of better phrasing humbled carver in some way, but I have a feeling because of what we've said about his personality and what I know about him. He was probably like, they're wrong. They just can't see this genius. Well, a visceral reaction from the critics, they cannot see this magic that is in front of them. Um,

Clay McLeod Chapman 47:14

someone out there, please, I'm talking to you, whoever you are out there. Correct me if I'm wrong on this story, because I feel like it is. I really want to believe in this story. So if I'm way off base, tell me now because I've been trying to tell this story to people for years, and maybe, maybe I've got it wrong at this point. But uh, yeah, yeah. Did you ever see Donnie Darko?

Michael David Wilson 47:45

Oh, yeah, I love Donnie Darko.

Clay McLeod Chapman 47:48

Did you ever see the Donnie Darko Director's Cut? I

Michael David Wilson 47:52

heard about the Donnie Darko Director's Cut. I have read about it extensively, but I haven't actually watched it. But yeah, have you watched it?

Clay McLeod Chapman 48:03

I have. And it you know, I don't know if I'm like trying to make an argument that like directors need other people to tell them what to do. Because I'm not I'm not saying that. But I do feel like it's always interesting. When it's like, look at the Director's Cut versus the theatrical release. Or, like, like I love I think I love the orig I'm when I was in my 20s and I first saw Donnie Darko, I loved the theatrical cut. And then and then to be given the kind of privilege the opportunity to like, have a director's cut, like oh my god, and then be like, Oh, that's what that was, like. Like, the shape of Donnie Darko was lost to me that the kind of it became a kind of amorphous state that like it lost some of its contours in a way that I felt. I really, I it left me kind of wanting the original. But yeah, that's a that's a digression. Because I'm, I'm like, trying to make this argument in my head right now of like, when is when is it good to have people on your side? You know, telling like, like, kind of focusing on like, making that thing, versus like the unbridled like, I you know, I'm calling the shots. I don't need anyone else's. I don't need an editor dammit. Don't tell me how to cut this movie, or this book.

Michael David Wilson 49:42

Yeah, I think we've Donnie Darko in particular, one of the things that makes the first iteration so fascinating is that there are multiple readings there are multiple interpretations of the film. And like a lot of good films that ambiguity leads to these fascinating conversations where you can never 100% say this person's interpretation is right, you can choose the interpretation that you think aligns best to the story and aligns best to your point of view. But there will always be that room for ambiguity. Whereas with the Director's Cut, it's like, this is the story. This is what happened. Yeah, there is no room for ambiguity. And so I would argue, and some people would disagree with this. But I think films and books are better when there is a level of ambiguity when there are multiple interpretations. Now, of course, in storytelling, you have to answer central questions, you have to close, you know, most of the plot, but it's like, let the even if it's just a minor thing, let's leave something open to interpretation lens, leave something partially answered or answered in such a way where you can question, you know, was this actually what happened? And I think, you know, some would say, that Shutter Island, the movie is superior to the book, because the movie has ambiguity as to how that ends and what is going on, whereas the book gives you a pretty clear cut answer.

Clay McLeod Chapman 51:42

Yeah, it's true. Um, God, I love Why do I love the movie Shutter Island so much? I want that is like such a comfort film to me. Like, if it's on, if I see it, I just I just find myself wanting to watch it. Yeah, they're minor digression. I. Yeah, you know, to your point, like, you know, with Donnie Darko, the Director's Cut explains everything, almost everything. And it's like, it takes away the ambiguity to such an extent that it takes away my interpretation of it. And all of a sudden, it's like, oh, man, now you're telling me what you think the story is. And it's negating my personal experience with the original cut? And therefore, like, Was that wrong? Like, was I wrong? And it's hard. It's a little bit like, and like, you know, I know, we're saving What kind of mother talk for our two. But like, I, I feel like I kind of programmed a bit of the kind of level of ambiguity that's in that book is confounding for certain readers, like people are really kind of angry at it for being as ambiguous as it is. So like, yeah, it's like, it's a strange kind of balance, right? Like you want to, you want to lead people towards an interpretation. And then you want to kind of allow that interpretation to be correct. So that a million people can have a million different interpretations of the same source material, the same book, the same movie, the same, whatever. But like, you're right, and you're right, and you're right. And like, everybody's right, because the filmmaker has made it so or the novelist has made it so that like, it's, it's permissible to have those interpretations, and no one is right, more than the other. But it's yours. I don't know. Like, that's, I love it when a book or a movie allows me the chance to kind of be like, well, this is what I think. Without telling me no, this is what this is what it is. This is what it's really about. Yeah,

Michael David Wilson 54:04

yeah. Well, you mentioned Paul Tremblay earlier and I think again, that is one of the things that makes a head full of ghosts such a brilliant story because you can read this on a supernatural level or you can read it on nothing supernatural happens. It works both ways. It

Clay McLeod Chapman 54:25

totally does. And it's so like, like, all the way to them is it is it really is or not, is it is it not? And I I just love it. And that's why like, you know, I think a head full of ghosts is a great example of ambiguity and the kind of tension that that creates. Where like I I feel like I'm pallbearers club. The ambiguity of that really made a lot of or I guess, like a certain cross section of readers really angry. Like, they were mad at him for that. And I just found that like, so amazing that like, he's kind of, I don't know if this is true, but like, I imagine him kind of relenting a certain. Like, he is in control of that book. But he's, he's kind of like, relaxing his grip on it to the extent that like, it's permitting readers to kind of come in and have their interpretation. And they want to look to Paul, and they want to ask him like, is this what is this what's happening? Is this right? Am I right in assuming this is what it is? And Paul's like, Hey, man, I don't know what do you think? And like, they get mad at that they get mad at him for that. I've read some of those Goodreads reviews and those those Amazon reviews. And it's astounding, like how irked people can be when they have the privilege to come to interpret a material and not have it like tied in with a nice, neat bow. Friggin the pallbearers club is like the most ambiguous book of that like scale that I've read in a long time. And I just love it. And people are so like, it's like, it's phenomenal. Like ah, kudos to him. And

Michael David Wilson 56:26

then the pallbearers club is the most divisive, Paul Tremblay book. And, of course, that's the ambiguity. But I think another reason why it's so divisive is now of course before he wrote horror, he was right in crime fiction, but then very much with a head full of ghosts and the success of that is cemented Paul Tremblay, as the horror guy with things like the cabin at the end of the world and survivor sung that just went towards saying, You know what, Paul Tremblay is horror. But then with the pallbearers club, it was like in the best possible way. He didn't give a fuck. He was like, I'm going to write this thing that, you know, you could essentially categorize as a fictionalized memoir, it is the quietest of his horror pieces, although there is obviously yeah, for very obvious reasons, horror within it, but it's so understated and subdued. It's like, it's like if everything else was the rock album that this is his acoustic set. Yeah. And it just seemed like he's doing this so confidently and in a positive way with little regard for how other people are going to take it as like, look, take take it or leave it. This is what I'm doing. And I think that is exciting, because that shows that every Paul Tremblay book, you won't know what you're going to get with it. And I think like actors might not like being typecast, I suppose, right? As don't always like being put into a box and being like, you're a horror guy. This is what you do. And it's like, well, yeah, surprise, motherfucker. Just what I do, and you got the pallbearers club? Yeah.

Clay McLeod Chapman 58:35

Oh my god. It also makes me think of Blade Runner. And the fact that like, what are we up to now there's like, four different versions for different director's cuts. There's like the theatrical release, there's the Director's Cut, there's the I think there's like something that called called, like, the ultimate cut, like there have been just so many different kind of versions of it, that it's actually it's a little confusing to me to kind of like, even know, what Ridley Scott assume, like says is the kind of like this is the definitive version, because there just been so many. And, and I feel like, I know, one version, he took out the, what is it that he took out the voiceover? Was it? Am I getting the story, right? In the original version, there's the voiceover and then he takes the voiceover out in the director's cut, or one of the director's cuts, and then it becomes more ambiguous as to like, what's going on and how the story unfolds. Am I telling the story right? I probably am not. And someone better take me to task for this. But like, I I just love the fact that like that movie, which in of itself, I think is one is a pretty ambiguous film. I I mean, there's an IT, there's like a road that leads you to an interpretation, if you so choose to kind of take it. But like by taking the the voiceover out, he's kind of permitting. He's like taking the training wheels off. And he's like, No, you got to ride this bike, like you got to, you've got to come up with your own interpretation, your own understanding of what this book this this, this film is. And that's scary for people. It's scary to interpret stuff. It's scary to like, because what if you're wrong? Like, what if I'm wrong? Like, what if? What if he's not a replicant? Like, is Deckard like, could I? Could I be wrong? Like, is that is it okay to be wrong? Like, that's what's great about interpretation is, is it a vampire? Is toppers club about vampires? Or is it not a vampire? Like, I don't know. Like, maybe maybe she's possessed. Maybe she's not possessed. I don't know. Like, you know, like, like, we want that bow so badly. We want things to be wrapped up so neatly that like, if there's no bow, if there's no gift wrap, like you're kind of, it's like, I don't know, you tell me man. Like, is it it? Is she possessed? Is it a vampire, is the replicant. It's so like, Oh, I got it's such a like privilege to be given that permission to do that. But like, on the reader side, on the audience member side, it's so scary. Because you want to, you want to be right. And you want to believe you want to get the ending that everybody else gets? So it's like, you know, you're you're kind of like, I think Deckard is a replicant. Am I right? I think I think she's a vampire.

Michael David Wilson 1:01:52

Yeah, I think as well, when I'm thinking about angry readers and angry critics, sometimes they can be annoyed, or they can say a piece of art is not good, because it wasn't the story that they wanted to be told. And it's like, yeah, but the story that you wanted, wasn't the story that the director or the writer or the filmmaker wanted to tell. So actually, when I first watched Jordan Theo's us, I was a bit disappointed when it turned into more a slasher movie, because I wanted to learn more about the family, I wanted to see the family dynamic and all that tension that was set up. But so for a while, I felt like, ah, US has disappointed me a little bit, but it's like, no, is a really good film. It's just not doing what you wanted it to do. And unfortunately, you know, Jordan, Peele doesn't consult me and be like, Is this okay? You're okay with that story? Mica let the one that you want. Probably doesn't even consult you and you've made a few with him.

Clay McLeod Chapman 1:03:10

But if you think of that moment in time, like what an interesting kind of nexus of in his in terms of his career, because like you were talking about reader expectations, audience expectations like to come off of get out with us. Like there is that moment that we all watched us for the very very first time and it undermined our expectations nearly at every step because everybody going into that movie wanted get out to or they wanted something they they wanted something kind of akin to get out and us is its own beast it's its own creation its own story that has kind of the genetic makeup akin to a similar to get I mean, it is a Jordan Peele film like you feel I feel like it you're you sense Jordan within it. But it is so wholly entirely its own that like you like you react to it in this kind of a, this is not good. It's like it kind of like you're reacting against it. It's like no, like, you want to kind of push back on it. It's like, No, this is I don't want this I want get out I want this. You're not giving me what I want. And like you're mad. You're mad at the movie. Which is why I feel like when you if you give it a second watch or a third watch, like make the movie. It's like the movie. It's like, it becomes what it is for you like it. It's like, you need to let get out go, you need to kind of like wash, get out off so that you can kind of come to us as this film, as you know, on its own terms. And I remember doing that with like, The Big Lebowski. I know this is a author, podcast and interview and I'm like, using all these references, forgive me. But like, everybody loved Fargo, the feature film like Fargo came out and it kind of like, it became its its own kind of pop culture moment. So the next movie that the Coen brothers did who i i love the Coen brothers. We go to see The Big Lebowski. And it's like, what is this? What is this thing that we're watching live like, it's like, it's a mess. It's a sprawling, kind of like, just fiasco. And it makes no sense. I don't understand it. And like, people were kind of like, grumpy about it. Like, they rejected it. They like pushed back against it. But to this day, every time I watch The Big Lebowski, it reveals itself to me in these ways, that are just so kind of like, miraculous. It's like so all inspiring, like, I love The Big Lebowski. And it's, it's just so kind of, it's interesting to me that, like, you can kind of watch something, and your audience expectations, your reader expectations are like, this is what I want. This is the story that I want. And this novel, this movie is not giving it to me, and I reject it, I push it, I push back. No, I don't like this. And it's such a bummer. Because it's not the movies fault. It's not Labelle skis fault. It's not the dudes fault. It's, it's the fact that like, we have these preconceived notions of what we want. That when the story tells itself, the way that the story tells itself. We're not accepting it on those terms. And that's, that's hard. Like, you have to let go, you have to kind of like meet each book, every movie on its own terms, even if it's the same author, even if it's like the Paul Tremblay of the Paul bears club is not the same Paul Tremblay of Survivor song. It's not the same as, as you know, Kevin in the end of the world, and like that's, that's amazing. That's amazing that he can kind of in reinvent himself with each book. But you as the reader have to kind of meet him halfway. You have to, you have to. You have to let go of a head full of ghosts, which is so hard. You want a head full of ghosts. I wanted a head full of ghosts. But he has to like you have to like get it out. Shake it out.

Michael David Wilson 1:08:16

Yeah, no, yeah. Thank you so much for listening to This Is Horror Podcast. If you want to get each and every episode ahead of the crowd, and support the podcast, please head over to www.patreon.com forward slash This Is Horror, and consider becoming our patron. Not only do you get early bird access to each and every episode, but you get to submit questions to the world's best writers. You can also listen to exclusive Patreon only podcasts, including story unboxed a horror podcast on the craft of writing, in which we unbox and dissect short stories and movies to patrons only q&a sessions with myself and Bob Pastorella, where we answer all of your questions writing related and otherwise, and the video cast on camera off record. And if that is not enough, you can also become a member of the writers forum over on Discord. So head over to patreon.com forward slash This Is Horror. Have a little look at what it is that we offer. Listen to the testimonials from others who are patrons. And if it looks like a good fit for you, then I'd love to see you there. Now another way that you can support the podcast absolutely free of charge is to leave us a review on Apple podcasts to write us on Spotify, or to follow us on social media. We are This Is Horror on acts formerly known as Twitter. And we are This Is Horror Podcast on tick tock for video clips and little bites of motivational goodness, and a splash of humor. You can also sign up for our newsletter at this is horror.co.uk. And if you would like to read my fiction, you can check out books including The Girl in the Video and House of bad memories. And if you want to read Bob Pastorella it's fiction. Do consider picking up a copy of mojo rising. You can also check out our collaborative novel They're Watching well okay with that said, it is now time for a quick advert break.

RJ Bayley 1:10:53

It was as if the video had on zips my skin slunk inside my tapered flesh and become one with me.

Bob Pastorella 1:11:02

From the creator of This Is Horror comes a new nightmare for the digital age. The Girl in the Video by Michael David Wilson. After a teacher receives a weirdly rousing video, his life descends into paranoia and obsession. More videos follow each containing information no stranger could possibly know. But who's sending them and what do they want? The answers may destroy everything and everyone he loves. The Girl in the Video is the ring meets fatal attraction from iPhone generation. Available now in paperback ebook and audio. House of bad memories the debut novel from Michael David Wilson comes out on Friday the 13th this October via cemetery gates media. Danny just wants to be the world's best dad to his baby daughter. But things get messy when he starts hallucinating his estranged abusive stepfather Frank, then Frank winds up dead and Danny is held hostage by his junky half sister who demands he uncovers the cause of her father's death with Danny to feed his demons or be perpetually tortured for refusing to answer impossible questions. Clay McLeod Chapman says house of bad memories hit so hard you will spit teeth out once you're done reading it. Preorder house of bad memories by Michael David Wilson and paperback at cemetery gates media.com or an e book via Amazon

Michael David Wilson 1:12:15

Well, that about does it for another episode of This Is Horror. Next week Clay McLeod Chapman will be rejoining us for the second and final part of the conversation. But until then, take care yourselves. Be good to one another. Read horror. Keep on writing and have a great, great day.